By Julie Rine, Minerva Local Education Association

“This would be the perfect day for a school shooting.”

“This would be the perfect day for a school shooting.”

My colleague whispered those words to me during AIR testing week, and followed it up with the equally chilling statement, “I have that thought sometimes. I hate it.”

She felt that way because we were all out of our routine in classrooms that were not our own, monitoring tests with kids who were not our own students. If anyone had really had the evil inclination to inflict violence upon those at our school, the controlled chaos already in place due to testing could have made us an easier target. When I started teaching, these thoughts would have seemed ludicrous.

I was 26 years old when I went home after school on a sunny April day in 1999 and turned on the TV to see students running from Columbine High School. Their arms were raised; their faces were showing the effects of seeing a familiar place of safety and comfort become a place of horror and fear. This was before I was a parent myself, so it was strictly as a teacher that I tried to put myself in that situation. The thought of hearing gunshots in my school or witnessing one of my own students use a gun against me or his peers was unimaginable.

Schools changed forever after that day. Lockdown drills have become just as common as fire drills. And they’ve evolved; we’ve adjusted our plans after every new school shooting and tried to imagine every possible scenario. Our classrooms now have medical supplies, “just in case”. We teach our kids to ignore the fire alarm unless they’ve been told to leave, because it could be a ruse to get them to run out of the building and into the path of the evil that wants to hurt them. We’ve practiced making an all-call announcement from our cell phones to alert the school of an active shooter, and we have shut down stairways or hallways during drills to force kids to think on their feet and escape by a different route.

We’ve gone from locking the door and sitting in silence against the wall, to fighting back and/or running, to barricading the door and arming ourselves with wasp spray, heavy textbooks, and scissors. During the first week of school, high school teachers ask kids to identify potential weapons in the classroom that could be used to defend ourselves in the worst case scenario. Elementary teachers have been trained in how to get little boys and girls to be quiet while they are hiding in cubbies or closets. Universities have an “emergency lock down” key hanging on classroom walls. We’ve gone from a “this will probably never happen but just in case” mentality to “we have to be prepared because this is much more likely to happen than we ever thought”.

I’m a parent now, and I’m grateful that my school district takes the threat of violence within our schools seriously. I’ve talked to my 7th grade daughter about how to decide if she should run, hide, or fight, and that conversation is not one I could ever have anticipated back in 1999. This summer, a photo went viral of a 3-year old girl standing on a toilet. Her mom took the picture thinking her daughter was being mischievous, but when she asked her what she was doing, the little girl in the pink and yellow nightgown told her mom she was practicing a lockdown. My 12-year old daughter and this little 3-year old girl are growing up in a world where preparing for this kind of violence is matter-of-fact, just part of their reality.

I have a few opinions about some changes that could be made in how we regulate guns in this country, but for every idea or proposal there is a counterargument. Some of my best friends and family members are very “pro-gun” and they make logical arguments to me when we discuss this issue. People who own and love guns are not inherently “bad’, and neither are people who desire stricter gun laws.

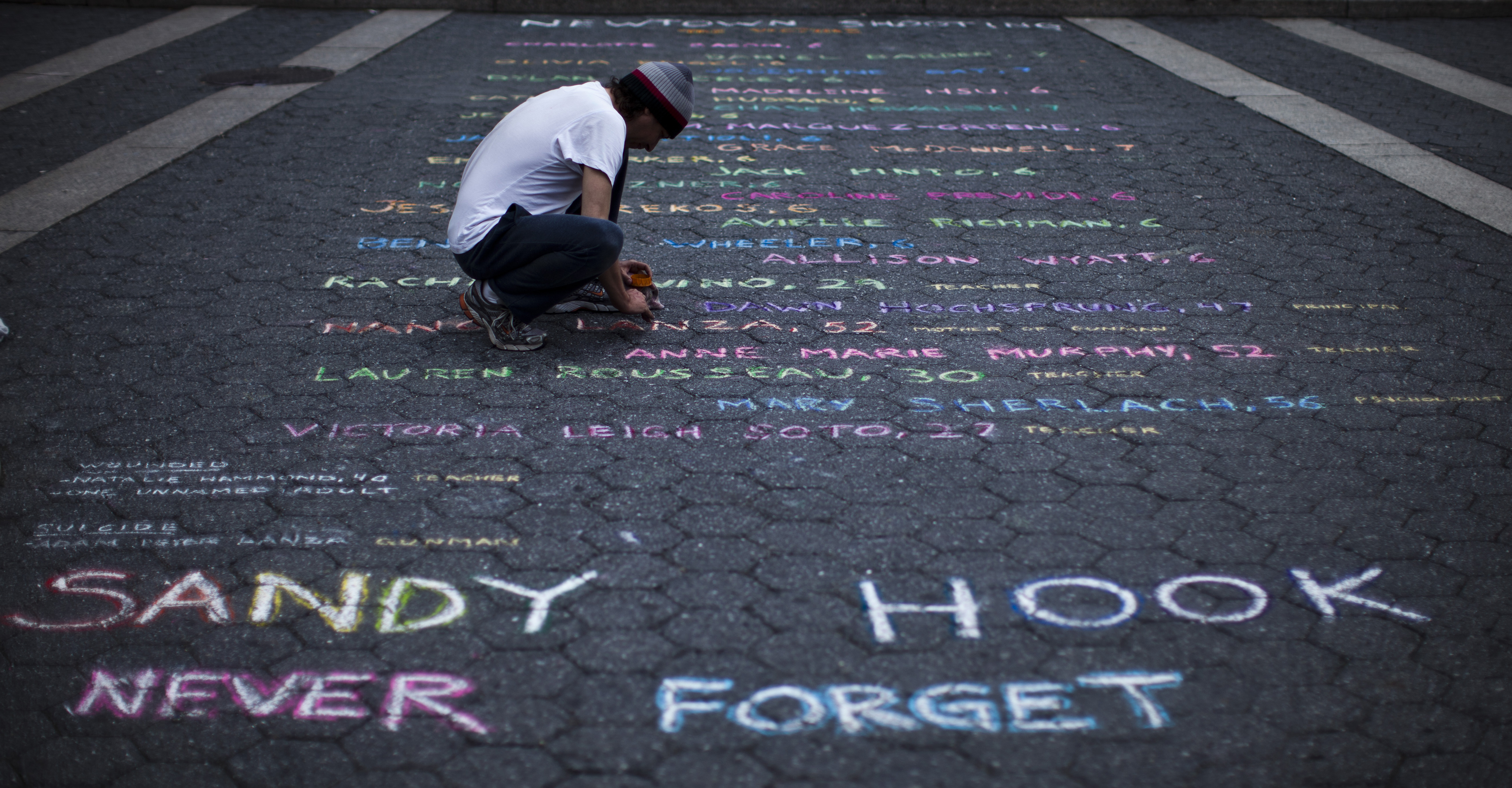

Still, something must be done beyond repeatedly adapting lockdown drills. Twenty innocent children and six adults died in the Sandy Hook shooting in 2012, yet nothing has really changed since then. Some argue that our country is simply “too far gone” to make adjustments in how we buy, sell, or regulate guns; some contend it would take too long to affect real change.

I don’t buy it. Our society can change because our society has changed. Twenty years ago, if I had told my students we were going to do a lockdown drill, they wouldn’t have known what I meant. Twenty years ago, the word “Columbine” wasn’t known to many people outside of Colorado, and if it was, it was known as a flower. Twenty years ago, my friend wouldn’t have shivered as she looked around and told me that it would be a good day for a school shooting.

We are raising a generation of kids who are well-aware of the dangers they face at school and outside of school. These kids don’t even walk around in fear the way we adults might; to them, gun violence is so commonplace, it has become normal. They know they can be shot in a movie theater or at a dance club or in their own school. We have come to expect what we wish we could avoid, while our leaders avoid what we wish we could expect: change. My truest desire is that our country will find some middle ground, some compromises, some way to keep the 2nd Amendment intact while making our country and our schools safer for our children.

When I retire in another 20 years, we might still have lockdown drills, but wouldn’t it be nice if they were as obsolete as WWII duck and cover drills are today? At the end of my career, I would like to leave a note to the teacher who takes my place telling her about all of the great people she will encounter in my school, instead of a note telling her where the weapons and medical supplies are stashed.

Is that too much to ask?

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save