A Teacher’s Brain Following Yet Another School Shooting…and Yet Another Misguided Response by Legislators

By Julie Holderbaum, Minerva EA/OEA

Another school shooting? 19 students killed? And two teachers?

He bought the AR-15s legally, just days after his 18th birthday? And bought another weapon just a few days after buying the first, with a high-magazine clip? Doesn’t anyone besides me see that there should be a red flag in some system somewhere that signals local police to check this person out?

Would it have made a difference in this case? Maybe not…but we will never know, will we?

Is this for real? Is a local group really raffling off an assault rifle as a fundraiser for a youth program? Are they really asking kids to sell tickets for an assault weapon when kids were just slaughtered with the same type of gun, to the point of needing a DNA sample to be identified? I’m not sure if there is ever a right time for that sort of fundraiser, but less than a month after Uvalde?

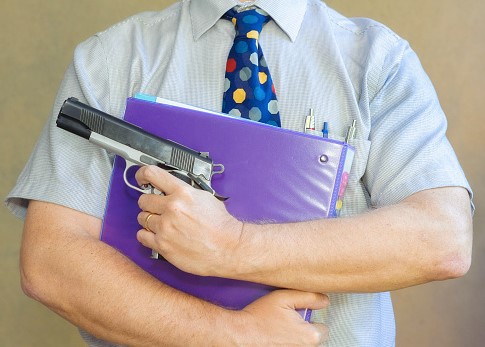

And now the legislature passed what? A bill to LOWER the number of required training hours to 24 for teachers to carry a weapon in school? Didn’t my daughter need 50 hours of behind-the-wheel training just to get a driver’s license? Why would a teacher, who is not in the field of law enforcement, need so few hours of training to carry a gun in a school?

How would that even work? Would it be a hand gun? Locked and loaded in a drawer somewhere? Is a handgun going to be any deterrent to a person carrying an assault rifle? Would I have time to get to it if I needed it? And how would I know I needed it? A loud noise in the hall? Would I get my gun and peek my head out to see if action is needed? Would eight other teacher heads be peeking out in my hallway, guns drawn?

If nothing was wrong and we grabbed our weapons in error, would the students in our classes be traumatized by seeing their teachers with loaded guns?

Or has this lockdown-drill-school-shooting cycle become so normalized to them that they wouldn’t even be phased at seeing the same people who teach them their ABCs or pre-calc wielding a dangerous weapon? And if so, what does that mean for the future of our country?

And what if the threat wasn’t in the hallway, but in my classroom? One of my students? Even if I could get to my gun, would I have the ability to shoot one of MY kids? Knowing he suffers from depression and can’t use our school resource mental health counselor because of insurance issues? Knowing his past experience with abuse? Knowing that he has not felt seen or heard or loved at home in years?

Could I shoot that kid?

And if I did use my gun, even if I saved lives, could I live with myself? What would the repercussions of pulling that trigger have for my own mental health? Would I ever be able to look at my students the same way again? Would they ever be able to see me in the same way again?

What if I hesitated? What if more were hurt because I struggled to pull the trigger? How could I ever teach again? How could anyone trust me again? How many lawsuits would I face because I didn’t act fast enough?

If trained law enforcement officers hesitated to enter Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, what makes anyone think teachers would be comfortable entering a spray of gunfire and endangering themselves? Especially with only 24 hours of training?

On the other hand, how many lawsuits would there be if I leapt into action, misread a situation, and shot an innocent person?

On the other hand, how many lawsuits would there be if I leapt into action, misread a situation, and shot an innocent person?

If we were required to actually carry our guns with us at all times, could I ever concentrate enough to teach effectively? How can I teach my students that words can change the world, that literature can move souls, that the power of a well-turned phrase can penetrate the hardest of hearts… while carrying a gun?

How’s that for a mixed message? Words have power, but guns are faster? Is that what we want to teach?

Beyond sending mixed messages, could I ever teach without constantly worrying about my weapon? About who is looking at it oddly today, about turning my back on anyone, about helping one student at her desk while my gun is about 2 feet away from the hands of the student in the desk next to hers? Would I have to keep one hand on my weapon at all times? As a TEACHER?

Surely I wouldn’t be required to carry a gun, though, right? I already check my classroom door multiple times a day to be sure it’s still locked; I already weigh the options of teaching with my door shut and locked for safety from shooters to teaching with it open to allow for more airflow and safety from COVID; I already jump at every odd sound or unannounced lockdown; how much worse would it be if I knew multiple people in our building were carrying guns?

This legislation won’t just affect the mental health of our students, will it?

I’m so tired of hearing that “the only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun”; if that’s true, why were weapons not allowed at the recent NRA convention in Texas? How could a room full of good guys with guns be a threat? Shouldn’t that be the safest place in the world? Why aren’t more responsible gun owners fighting for universal background checks, for a raise to the age limit to buy certain guns, for red flag laws, for a required waiting period before possessing a gun after purchase?

With so many Americans in favor of at least some reform to gun laws, are legislators who refuse to advocate for safer gun laws just afraid of losing their jobs? Afraid that without the money of the NRA and other pro-gun lobbyists they won’t be able to fund a successful campaign? That they would lose their power, their position, their ability to provide for their families? But don’t those same legislators force educators to live with those fears every day, knowing that if we teach about racism or other sensitive topics in the wrong way, we could lose our jobs thanks to their laws?

If they think we can’t be trusted to discuss elements of America’s troubled past or the current events of the day in a responsible manner, why would they deem us responsible enough to carry a gun in school?

When will our politicians put people over power? When will they set aside pride to work with the other side? When will the safety of our communities take precedence over an election?

If the politicians currently in office aren’t willing to make changes, is the blood of the victims of the next shooting on their hands….or on ours?

If this isn’t the time to persist in our efforts to persuade responsible gun owners to join the cause, when is?

If this isn’t the time to promise our children that we will do more than pause to remember the victims and pray that this never happens again, when is?

If this isn’t the time to preserve the sanctity of our classrooms as places of learning, belonging, and growing, when is?

If this isn’t the time to pursue real action by promoting politicians who run on a platform of actual changes to the law, when is?

If this isn’t the time to protest, when is? Aren’t the protest signs true? “The power of the people is greater than the people in power?”

Isn’t the truest form of political protest voting out those who have made empty promises but not practical efforts at positive change?

How many days until November?

Small Moments of Joy: Can They Keep Teachers in the Classroom?

By Julie Holderbaum, Minerva EA/OEA

On March 17, 2020, I wrote about what it was like to be a Type A Teacher in the uncertain times of the statewide school shutdown. I described how I was clinging to what I knew for certain: that this was an opportunity to refocus on the kids instead of standards or testing, and that our kids needed us more than ever.

As it turned out, the next school year was even more daunting. Some of you were still teaching through a screen, trying to make and nurture human connections with kids you had never met. In my district, we were teaching while wearing masks and sanitizing everything, in person every day but still trying to post as much online as we could for the kids who were at home sick or quarantined. And some of you were in what Dante would surely consider a special circle of hell, teaching online and in person at the same time.

As it turned out, the next school year was even more daunting. Some of you were still teaching through a screen, trying to make and nurture human connections with kids you had never met. In my district, we were teaching while wearing masks and sanitizing everything, in person every day but still trying to post as much online as we could for the kids who were at home sick or quarantined. And some of you were in what Dante would surely consider a special circle of hell, teaching online and in person at the same time.

Last spring, a year into COVID, I wrote about changing my perspective from doing everything possible to get the job done to doing everything possible to keep myself healthy and sane. I wrote that “We can’t possibly hope to produce flourishing students if we aren’t even attempting to flourish ourselves. Sometimes you don’t do what you gotta do to get the job done; you do what you gotta do so that you can keep doing the job.”

When the end of the 2020-21 school year came, the vaccine was widely available. My teacher friends and I celebrated mightily on that last day of school. We were looking forward to a well-deserved break and a return to normal for the 2021 school year. There was joy in the air.

Well. Here we are. Fall of 2021. Not much joy, is there?

COVID still rages. School leaders and teachers are forced to reconsider, once again, how we do everything, from teaching, to athletics, to dances, to extracurriculars, to parent/teacher conferences, to assemblies. It seems every day there is a new decision to be made.

Community support has waned. Parents are attending school board meetings, angry about mask mandates. Frankly, it is absolutely demoralizing to hear people berate teachers and schools for trying to do what’s best for kids, or even worse, accuse us of not caring about kids. We are fighting for the safety and well-being of our students and we are being browbeaten for it.

![]() Politicians are debating what part of the truth we are allowed to teach our kids, accusing us of indoctrinating our students when we are merely trying to give them the whole picture. Isn’t it our job to teach America’s full history, not just the parts that make our country look good? We teach our students how to have a respectful conversation about difficult topics with people they disagree with in a safe space. What’s going to happen if our children don’t learn these lessons? We certainly won’t become a more inclusive, rational, respectful society, will we? And I’m pretty sure I know who will get blamed for that.

Politicians are debating what part of the truth we are allowed to teach our kids, accusing us of indoctrinating our students when we are merely trying to give them the whole picture. Isn’t it our job to teach America’s full history, not just the parts that make our country look good? We teach our students how to have a respectful conversation about difficult topics with people they disagree with in a safe space. What’s going to happen if our children don’t learn these lessons? We certainly won’t become a more inclusive, rational, respectful society, will we? And I’m pretty sure I know who will get blamed for that.

Add to all that the Ohio politicians who want to give parents of K-12 children voucher money so they can leave public schools if they disagree with any aspect of their local district from curriculum to policy.

Joy, excitement, energy…school year 21-22, at least for me, has seen less of those than any other year of my career.

I know that my particular situation is a good one. I have great students who give me grace when I have a bad day. I have wonderful colleagues. The parents from our town who attended our school board meeting to oppose the mask mandate did not get violent and were not disrespectful. Our staff feels respected and appreciated by our administration more than many other teachers do around the state.

And yet, this school year, I’ve seriously considered leaving the profession.

The problem is, I’m an English teacher trying to work out a math equation: is COVID + increased disrespect from society + political agendas + the usual stresses of a teaching job equal to or greater or lesser than caring about the kids and the future + occasional moments of joy? Factor in decades invested into a retirement system and the importance of having good healthcare and the equation gets incredibly complicated.

I’ve thought about what has brought me to this point. Is it just the stress of COVID? Maybe it’s the fact that I’ve taught for two and a half decades in Ohio and still haven’t seen fair school funding be made a priority of our legislature. Maybe it’s because the legislature continues to show a disregard and distrust of what we teach and how we teach it. Maybe it’s because the Ohio State Board of Education just repealed an anti-racism resolution passed last year. Maybe it’s because even COVID didn’t derail the standardized testing and data train. Maybe it’s because my salary is still not commensurate with other equally degreed college graduates. And maybe I could deal with all of that if I only had five years to go before I could retire, but because of STRS changes since I began my career, I have twelve, and being the kind of teacher I want to be, one that I can be proud of, for 12 more years seems unfathomable to me.

I’m not alone. A recent study by NEA shows that 32% of teachers are planning to leave education earlier than they originally planned.[1] Something’s got to give, or we are going to lose a lot of good teachers.

Resilience doesn’t just mean adapting well in the face of adversity, being in a terrible situation and sticking it out. Resilience is elasticity; the ability to bounce back. If the current state of education in Ohio is one that is endangering my ability to bounce back, to retain the core of who I am, to be the kind of person I want to be, then it’s not a path I can continue on. Last spring I wrote that “I still have what’s most essential to being a good teacher: I still care about the kids.” This year, I’m wondering if caring about the kids means knowing when it’s time to put them in someone else’s hands.

I’m not quite there yet. But part of taking care of myself in this third year of teaching during COVID means not just getting through each day, but examining how I want the rest of my days to be, as a person, not just as a teacher. It means being open to the idea that I might not retire at the end of my working years from teaching as I had always assumed I would. I’m not quite at the end of my rope, but the end of my rope is fraying, quickly.

I’m not quite there yet. But part of taking care of myself in this third year of teaching during COVID means not just getting through each day, but examining how I want the rest of my days to be, as a person, not just as a teacher. It means being open to the idea that I might not retire at the end of my working years from teaching as I had always assumed I would. I’m not quite at the end of my rope, but the end of my rope is fraying, quickly.

There is some comfort in knowing I am not alone. Just last week in an ECOEA meeting, colleagues in schools all around me discussed feeling the same way. In addition, Cult of Pedagogy dropped a new podcast entitled “Teachers are Barely Hanging On. Here’s What They Need”, and a Michigan teacher/writer I love, Dave Stuart Jr., wrote about the struggle of teacher burnout. So many educators are seeking solutions to the problems that plague us. We are fighting for our profession. We want to find the joy again.

And sometimes, we find it. Last week on Tuesday, I did not get one paper graded or lesson planned during the school day, but I left school feeling lighter and happier than I had all year. Why? I spent my planning period and some time after school having unplanned one-on-one conversations with students. One needed someone to listen, to acknowledge what he’s been through and to affirm that he was on the right path. The other needed a nudge to make a plan for moving forward, a little support and guidance and direction. Those conversations reminded me of why I chose teaching in the first place.

There haven’t been many days this year when I’ve felt that I’m in the right place at the right time, but on that day, I felt that I was right where I was meant to be.

I hope that the challenges of teaching this year are growing pains and that the struggles we are facing will lead to meaningful changes, because I need more days like that.

We all do.

— Julie Holderbaum is an English Instructor and an Academic Challenge Advisor at Minerva High School, Minerva, Ohio.

[1]“Educators Ready for Fall, But a Teacher Shortage Looms | NEA.” 17 Jun. 2021, https://www.nea.org/advocating-for-change/new-from-nea/educators-ready-fall-teacher-shortage-looms. Accessed 11 Oct. 2021

Doing Whatever It Takes: A Changed Perspective

By Julie Holderbaum, Minerva EA/OEA

Henry Darby, a principal in South Carolina, recently made headlines for working an overnight job at Walmart so he would have extra money to help the students in his community. Why? According to Darby, “You just…do what you need to do.”1

I think I’m supposed to have warm, gooey feelings when I hear about stories like his, so why did it depress me so much?

Maybe because this year, I have had little energy to do much beyond show up to work on time and put forth a solid effort during the day. I leave as soon as I am contractually allowed to leave, and outside of a few weekend afternoons grading at home, I’ve not spent time doing school work after 2:30 PM each weekday.

It didn’t used to be this way. Like Mr. Darby, I would do whatever it took to get the job done and done well, even if that meant grading or planning in my home office instead of spending time with family, or spending my own money on supplies for my students. Even when not in school, it was not unusual for my brain to be constantly whirring with thoughts of lesson plans or students or activities or curriculum pacing or technology or state tests or any of the countless number of aspects to a teacher’s job.

It didn’t used to be this way. Like Mr. Darby, I would do whatever it took to get the job done and done well, even if that meant grading or planning in my home office instead of spending time with family, or spending my own money on supplies for my students. Even when not in school, it was not unusual for my brain to be constantly whirring with thoughts of lesson plans or students or activities or curriculum pacing or technology or state tests or any of the countless number of aspects to a teacher’s job.

But this year, I’ve started to wonder if I have the energy to make it to retirement in a teaching career. National news stories heralding extraordinary educators like Mr. Darby only make me question myself even more. A few times, I’ve caught myself wondering if it’s time to consider getting out.

I’ve come to realize, though, that in spite of the stress of teaching through COVID, I still have what’s most essential to being a good teacher: I still care about the kids.

Of course I get frustrated with my high school students at times. But the fact remains, I want them to become flourishing adults who contribute meaningfully to their communities. I want them to be able to think and read critically, to fight with passion for their beliefs and to listen with compassion to those who hold opposing points of view. I want them to recognize the importance of finding the balance between living every day as if it’s their last and as if they will live forever. I want them to learn to approach each day with intention, putting forth an effort they can be proud of, even if the day consists of the mundane routine of going to school and home again.

Those desires fuel every lesson I plan, even this year, when literally surviving is my main goal.

When the pandemic hit almost a year ago and we had to start teaching from home, I learned very quickly that I was going to have to work to keep my anxiety at bay. I exercised daily. I read for enjoyment. I did yoga. My family and I worked puzzles. I watched the news only once per day and limited my time on social media.

When school started this fall, my district decided to go back face-to-face, five days a week. I’ve had to keep up the practices I started last spring in order to take care of my mental well-being. Consequently, I’ve had no extra time to put into my job, and frankly, the stress of being in school saps my energy for even thinking about school when I’m not there.

One of the newscasters telling Mr. Darby’s story wondered when he had time to sleep. It’s a good question; what he is doing is most likely not sustainable for a long period of time, no matter the depths of his love for his students. We need to realize that teaching is an exhausting job whether we are experiencing a pandemic or not, and whatever we do to get the job done needs to be something we can continue to do for the long haul.

I am not questioning Mr. Darby for working that second job, nor am I criticizing teachers who grade papers on the weekends or stay late after school or provide supplies for their students. We need people like that. But maybe we need to take turns being people like that. And we need to recognize that it’s okay not to be people like that.

I am not questioning Mr. Darby for working that second job, nor am I criticizing teachers who grade papers on the weekends or stay late after school or provide supplies for their students. We need people like that. But maybe we need to take turns being people like that. And we need to recognize that it’s okay not to be people like that.

Maybe we need to question why teachers feel pressured to sacrifice whole chunks of their lives to their job outside of regular work hours.

Maybe we need to question why teachers who take care of their own mental health aren’t as highly glorified in the media as teachers who run themselves ragged trying to make up for the shortcomings of our society. Where are the stories about teachers who figure out how to leave school at school, who work like dogs during the day so they can come home at night and hit the mat for some downward dogs?

Maybe we need to question why, in 2021, in any state in this country, funding for public schools is so egregiously inadequate that a principal would even consider getting a second job to make more money to provide for his students. We certainly need to question why here in Ohio, our legislators just can’t ever quite get around to fixing our state’s unconstitutional school funding system. What are our legislators prioritizing over our kids? And why?

Society has always faced more questions than answers when it comes to dealing with public education, but this year, the question that has haunted me is whether or not it’s time to leave education. To answer that question, I had to ask another: do I want to continue to be an educator? The answer is a resounding yes, so I must do whatever it takes to allow myself to keep showing up for those teenagers who I still care about so much.

COVID has changed the way every American is able to perform their job, whether that job is in a hospital or a grocery store or an office or a classroom. We are all facing situations for which we have not been trained or adequately prepared. Teachers certainly aren’t the only ones dealing with higher levels of stress than usual. But society has always asked teachers to live up to extraordinary expectations, and we aren’t all Louanne Johnson or Erin Gruwell; being a good teacher, even an exceptional teacher, doesn’t always mean accomplishing feats that are big-screen worthy.

COVID has changed the way every American is able to perform their job, whether that job is in a hospital or a grocery store or an office or a classroom. We are all facing situations for which we have not been trained or adequately prepared. Teachers certainly aren’t the only ones dealing with higher levels of stress than usual. But society has always asked teachers to live up to extraordinary expectations, and we aren’t all Louanne Johnson or Erin Gruwell; being a good teacher, even an exceptional teacher, doesn’t always mean accomplishing feats that are big-screen worthy.

For many years of my career, “you do what you gotta do,” meant doing whatever it took to get my job done. Now, it means doing whatever I have to do to take care of myself physically, mentally, and emotionally, and not letting my job or the stress that comes with it overtake the rest of my life.

During a pandemic or during a “normal” year, if you’re doing your job as well as you can within school hours and then letting it go, it’s okay. We can’t possibly hope to produce flourishing students if we aren’t even attempting to flourish ourselves. Sometimes you don’t do what you gotta do to get the job done; you do what you gotta do so that you can keep doing the job.

— Julie Holderbaum is an English Instructor and an Academic Challenge Advisor at Minerva High School, Minerva, Ohio.

[1]High school principal works overnight at Walmart to … – Yahoo News.” 29 Jan. 2021, https://news.yahoo.com/high-school-principal-works-overnight-153343899.html. Accessed 2 Feb. 2021

To Vote or Not to Vote: Why Educators Need to Do More Than Help Students Register to Vote

By Julie Holderbaum, Minerva EA/OEA

On a recent visit home, my 22-year old stepdaughter told me that she wasn’t planning to vote this year, and then she admitted that she never had before, either.

As we talked, two reasons for this came to light. Apathy was not one of them. Instead, not knowing what to expect at the polls, not knowing which local candidates would be on the ballot, and feeling that her vote wouldn’t matter anyway were enough to silence her voice.

She expressed that she was really nervous to go to the polling place because she had no idea what to expect. I have always emphasized the importance of registering to vote to my students. I’ve even helped register several voters in my classes of juniors. But in my haste to register my students to vote, it never occurred to me to explain to them what the actual act of voting would be like.

She wasn’t too worried about not going to vote since the 2016 election convinced my stepdaughter that her vote wouldn’t matter anyway. I can see why she felt that way; Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by 3 million votes but lost the election because she came up short in the electoral college. The fact is, however, that history is replete with elections decided by one or a very few votes. In Vermont in 2016, both a state Senate Democratic primary and a state House seat were determined by one vote[1], and several presidential elections have been narrowly decided as well[2].

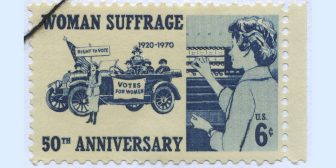

My stepdaughter’s revelation to me was heartbreaking. I hated the thought of her not exercising the right that so many people fought so hard to get, the right that gives her a voice in choosing the values and policies of the community and country she lives in.

Many educators discuss the importance of voting with our students. But can we do more to alleviate their anxiety and fear of the unknown, to make them feel that their voice matters? I think we can.

- Share your first time voting story. You don’t have to disclose who you voted for to tell students about where you were and how you felt. Did you vote in person or absentee? Did you feel prepared to vote? What did it feel like if you didn’t know anything about candidates on the ballot? I tell them how I’ve felt when I’ve seen names on a ballot in local races and not known anything about them: do I pick one at random or do I not vote in that race? One seems risky and the other seems disrespectful to all those who have fought for my right to vote. I also tell them that it feels so much better to know I have done the research and am voting for a person (or issue) with intention.

- Explain the voting process. Encourage them to let the poll workers know it is their first time voting; most likely, they will be excited and happy to help them navigate each step of the process. Tell them that they will show their ID and it will be scanned, and they will sign either a paper or an electronic keypad. They will be directed to the voting booth, which may or may not have a curtain like the voting scenes on TV always seem to. They may vote on a computer. They might be given a paper ballot and a pen to bubble in their choice. They may be given a punch card to indicate their choices. Tell them that they do not have to vote in every race on the ballot. Whatever the method, reassure them that it will be private and no one will see how they vote. Discuss the importance of completing absentee ballots thoroughly and correctly, and following all directions precisely.

Discuss the history of the fight for suffrage in America. Only 6% of Americans were eligible to vote in the first presidential election.[3] The other 94% had to fight to get the right to participate in democracy in America. Read articles and show movies about efforts to get the right to vote and the obstacles that still impede efforts to vote for so many Americans. The 2020 Amazon Prime documentary All In: The Fight for Democracy is excellent and gives a history of voting rights and suppression efforts in America. (Preview any film before showing your classes).

Discuss the history of the fight for suffrage in America. Only 6% of Americans were eligible to vote in the first presidential election.[3] The other 94% had to fight to get the right to participate in democracy in America. Read articles and show movies about efforts to get the right to vote and the obstacles that still impede efforts to vote for so many Americans. The 2020 Amazon Prime documentary All In: The Fight for Democracy is excellent and gives a history of voting rights and suppression efforts in America. (Preview any film before showing your classes).- Impress upon your students that every vote counts. Read about elections that came down to just a few votes. Share the fact that studies show more people vote when they know lots of other people are voting. Tell your students that publicizing they are voting can remind and encourage others to vote…and all of those votes will certainly have an impact.[4]

- Demonstrate how to find information about the candidates, registration, and polling places. Today’s young voters have advantages that I did not when I first voted. Websites for each state’s Secretary of State and County Boards of Elections have information about how to check if your voter registration is up to date and more. The Ohio Voter Info app [5] allows users to see a sample ballot, making it easy to research the candidates and issues before going to the poll. The app also allows users to check absentee ballot status, see where their polling place is, and view election results. When We All Vote is another great resource, and the website has a toolkit for schools to teach kids of all ages about voting.[6]

- Build excitement for future voting in children. What if we could get kids to look forward to their first time voting as much as they look forward to getting a driver’s license or going to prom? If we start talking about voting with young children, I think we can build a level of excitement and appreciation for the right to vote. There are books for all ages of children that address elections and voting.[7] Make them part of your classroom library.

Along the same lines, take your own children with you when you vote. I have taken my daughter with me since she was four years old, and every time, I have explained to her who I am voting for and why. The familiarity with the voting process has become ingrained in her. Encourage your students to ask their parents if they can go with them the next time they vote so they can see the process of voting in action.

Political conversations in the classroom that promote issues or candidates are never appropriate, but the act of voting is not a partisan issue. It is our duty as educators to prepare our students to become informed citizens who participate in the democratic process. We must remember, however, that it doesn’t matter how many students we register to vote; the only ones who have a voice are the ones who actually exercise that right. We need to go beyond registration efforts and address the concerns and fears young voters have about the actual act of voting.

During that infamous visit, my stepdaughter and I updated her voter registration and downloaded the Ohio Voter Info app. She knows where she is going to vote and which issues and candidates will be on her ballot. She’s ready to vote in one of the most historic elections in American history this November.

The best part? The next time she came home to visit, she had another announcement to make: “You’re going to be so proud of me. I helped my roommate register to vote.”

— Julie Holderbaum is an English Instructor and an Academic Challenge Advisor at Minerva High School, Minerva, Ohio.

[1]Close Elections: Why Every Vote Matters : NPR.” 3 Nov. 2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/11/03/663709392/why-every-vote-matters-the-elections-decided-by-a-single-vote-or-a-little-more. Accessed 5 Oct. 2020.

[2]“5 Close US Presidential Elections That Prove Every Vote Matters.” https://www.globalcitizen.org/fr/content/why-every-vote-matters-closest-elections-in-histor/. Accessed 6 Oct. 2020.

[3] “Watch All In: The Fight for Democracy | Prime Video.” https://www.amazon.com/All-Fight-Democracy-Stacey-Abrams/dp/B08FRQQKD5. Accessed 6 Oct. 2020.

[4] “A better argument for why every vote matters – The Princetonian.” 11 Oct. 2018, https://www.dailyprincetonian.com/article/2018/10/a-better-argument-for-why-every-vote-matters. Accessed 5 Oct. 2020.

[5] “Ohio Voter Information – Apps on Google Play.” https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.triadgsi.dev.ohiovotes&hl=en. Accessed 6 Oct. 2020.

[6] “When We All Vote.” https://www.whenweallvote.org/. Accessed 6 Oct. 2020.

[7] “Kids’ Books About Elections and Voting | Scholastic | Parents.” https://www.scholastic.com/parents/books-and-reading/book-lists-and-recommendations/history-social-studies/election-books.html. Accessed 5 Oct. 2020.

‘A’ is for Advocacy – Why We Must All Become Activist Educators

By Julie Holderbaum, Minerva EA/OEA

During the past few months, Ohio’s teachers have found ways to creatively teach every content area while being separated physically from our students. It hasn’t been easy.

However, our struggles as teachers learning new technology and methods of teaching pale in comparison to the challenges of our students trying to learn from home. Few of them have a quiet workspace with a computer and ample time to engage with school assignments. Even in the best case scenarios, students are distracted by Netflix and TikTok, phones and video games. Most of my students face even greater challenges. They are taking care of younger siblings while their parents work, or they are working more hours at their own jobs to help with family expenses. Some of my students suffer from depression and anxiety, and now they are dealing with the world turned upside down. Sadly, in the worst cases, students are trapped at home with physically or mentally abusive family members and no escape to the safety of school.

Coupled with the fact that the learning environment at home can be problematic is the fact that there is great inequity in access to technology among Ohio’s families. A significant number of our students do not have access to the internet or the devices necessary to complete online work even in otherwise positive home learning environments.

A packet of work sent home is not the same as students being able to participate in a class meeting online or exchange emails with their teacher. It’s not the same as being able to view videos of their teachers explaining concepts, or watching their teachers work a math problem or edit a paragraph via a document camera.

Given the stressors that make learning from home difficult and the lack of technology that plagues many students, we can all agree that in-person education is in the best social and academic interest of our kids (and, frankly, our economy, because not every parent has a job that allows them to work from home when kids are not in school).

The task before us then is daunting and expensive: we need to deal with the technology gap in case a public health crisis again forces us to educate through remote learning, while at the same time make accommodations to ensure safe conditions for in-person learning.

I was hopeful that Governor DeWine would avoid making drastic cuts to school funding. I was even naive enough to hope the governor would find ways to provide more funding to public education.

Instead, last week, the governor announced a “$300 million reduction in K-12 public-school funding, $210 million from Medicaid spending and $110 million from college and university funding.”[1] To my dismay, teachers, students, and the poorest Ohioans will bear the brunt of the budget cuts caused by the COVID-19 crisis.

Instead, last week, the governor announced a “$300 million reduction in K-12 public-school funding, $210 million from Medicaid spending and $110 million from college and university funding.”[1] To my dismay, teachers, students, and the poorest Ohioans will bear the brunt of the budget cuts caused by the COVID-19 crisis.

Interestingly, the Department of Corrections was spared from the budget ax, because “(prisons) have gotten to be more expensive to operate as state officials try to deal with COVID-19 outbreaks among prisoners and staff.”[2]

Aren’t schools going to become more expensive to operate as we try to deal with preventing outbreaks among students and staff? Schools are also a setting where a lot of people come in contact with each other in a relatively small space, which is why they were the first to be shut down when the dire nature of the situation became clear.

To return to school and keep our students and educators safe, nearly every aspect of the school day will need to be changed. Lunches, assemblies, large classes such as gym and choir, even one-on-one tutoring sessions will all have to be reconfigured. To achieve smaller class sizes, students might attend on alternate days or for half days. These modifications may require extra bussing, increased staffing, longer school operating hours, and at the very least, more daily cleaning and sanitizing. Furthermore, we need to be prepared to offer additional mental health services to help our students deal with the stress of returning to school or the trauma they endured while at home. Not knowing if or when something like this might happen again, we also need to ensure equal access to technology for all kids. And all of that equals MORE MONEY, not less.

Why not tap part of Ohio’s rainy-day fund? We are far beyond rain. We are past thunderstorms, tornadoes, and floods. We are close to “Sharknado” territory, and if that isn’t the time to use at least part of the rainy-day fund, when is? In actuality, we could use ALL of the rainy-day fund to avoid cuts in education and still have billions left over.

I know that OEA’s leadership agrees that we should tap into the rainy day fund. As Piet van Lier of Policy Matters Ohio noted “the state should have looked to the rainy-day fund now to help school funding, a move DeWine chose not to take,” and adding that “It’s just beyond comprehension that you could be doing that [cutting aid to schools] without turning over every stone.”[3]

Perhaps the cuts to school budgets made by the governor will be offset by the federal CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act. But the fact remains, if DeWine had not made the draconian cuts to education, any CARES money school districts receive could have actually been used to address the inequity issues and the need for creative solutions to resume in-person education, rather than to simply put local budgets on track to barely break even.

The governor likes to say we are “all in this together.” It doesn’t feel that way to me. It feels like educators, who have figured out how to completely change education in a matter of days, who are putting in more hours than ever before, who don’t even have time to say “we didn’t sign up for this,” are being taken advantage of. We’ve always stepped up, we’ve always figured out how to make do with the money we’re given, we’ve always done everything that has been asked of us and in such an outstanding manner that the governor has no reason not to expect that we won’t figure this out, too.

We simply have to stop settling for monetary leftovers. We have to fight to make Ohio’s children the priority they should have been all along. We can’t count on Betsy DeVos or the current occupant of the White House to provide federal dollars to help the nation’s schools meet the new challenges we face. We can’t simply rely on union leaders or education-friendly state legislators to advocate for us and for our students. WE must fight for funding to address the new needs of our schools. WE must fight for safe conditions for us and our students to return to. WE must fight for equal access to technology for all kids.

We simply have to stop settling for monetary leftovers. We have to fight to make Ohio’s children the priority they should have been all along. We can’t count on Betsy DeVos or the current occupant of the White House to provide federal dollars to help the nation’s schools meet the new challenges we face. We can’t simply rely on union leaders or education-friendly state legislators to advocate for us and for our students. WE must fight for funding to address the new needs of our schools. WE must fight for safe conditions for us and our students to return to. WE must fight for equal access to technology for all kids.

We must let the governor and our elected representatives in Ohio and Washington DC know that we are willing to step up to the challenge that the COVID virus has brought to education, as we have demonstrated in stellar fashion during remote learning, but we need financial help to do so.

It is time to go on the offensive.

There are nearly 140,000 educators in Ohio[4]; imagine the power of some 140,000 people advocating for proper funding to take care of the needs of our students. We teach our students to stand up for what they believe in; are we doing that ourselves?

It’s worth contacting our U.S. Representatives and Senators to ask them to fight for funding from Congress. We have an even better chance of developing relationships with our state representatives and senators. A hand-written letter speaks volumes. An email also works and will allow you to quickly reach all of your legislators. Put your legislators’ office phone numbers in the Favorites on your phone so you can call them easily and frequently. Donate to the FCPE fund so that we can continue to elect legislators who support public education.

We need to make sure our leaders are hearing from educational experts. They might not seek out our opinion, but we must give it to them anyway, and hope that they have the good sense to listen to us when making decisions that impact education in Ohio.

The old cliche says that teachers shape the future. That has never been more true than now. It pains my heart to say it, but education may never be the same. We may never go back to “normal.” We have to prepare for that reality, and that means becoming teachers who advocate and argue for the funding we need to make the changes that will indeed shape the future of public education in a post-COVID 19 world.

— Julie Holderbaum is an English Instructor and an Academic Challenge Advisor at Minerva High School, Minerva, Ohio.

[1] “Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine announces $775m in state budget ….” 5 May. 2020, https://www.cleveland.com/open/2020/05/ohio-gov-mike-dewine-announces-775m-in-state-budget-cuts-to-education-medicaid-and-more.html. Accessed 6 May. 2020.

[2] “Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine announces $775m in state budget ….” 5 May. 2020, https://www.cleveland.com/open/2020/05/ohio-gov-mike-dewine-announces-775m-in-state-budget-cuts-to-education-medicaid-and-more.html. Accessed 6 May. 2020.

[3] “Coronavirus economic fallout ‘terrifies’ school leaders, experts ….” 8 May. 2020, https://www.cleveland.com/coronavirus/2020/05/coronavirus-economic-fallout-terrifies-school-leaders-experts-stirring-fears-of-deep-budget-cuts-merged-districts.html. Accessed 11 May. 2020.

[4] “Facts and Figures | Ohio Department of Education.” 11 Feb. 2020, http://education.ohio.gov/Media/Facts-and-Figures. Accessed 11 May. 2020.