This Does Not Compute

My hands hovered over the keyboard as my brain caught up to what my fingers had just typed. Did I really just make that comment to a student? “The computer won’t know that this fragment works as part of your style; it will just see a sentence fragment and most likely will ding you for it.”

Even before responses were graded by computers, AIR tests were never looking for a piece of writing that demonstrated a unique voice and style, but rather a piece of writing that included enough elements on a checklist for the assessor to deem the text “proficient”. Still, with human assessors, there was the opportunity to wow the grader, to stand out from the other essays in some way. Now, I fear that essays that stand out too much might actually lose points for not aligning closely enough to the templates used to program the machine for that particular essay prompt.

In addition to worrying about writing a too-unique response for a computer, a student must also worry about not using enough original language in his response. 3rd Grade AIR test responses are being given zero points if there is too much wording from the question in the student’s answer. Many students are taught to restate the question to help guide their writing, but now, with machines scoring their work, that can result in a score of zero. Curiously, tests regraded by humans at the request of school districts are not seeing a significant number of scores changed. I wonder if we are training computers to grade like humans or, sadly, training humans to grade like computers.

Anyone not familiar with the high school AIR ELA tests might be shocked to learn that only 30% of the student’s response is expected to be original. That seems like a very low amount of original text. However, students are asked to read a few passages and then cite the passages extensively in their essay response. Indeed, four of the ten points possible on the essay are based on Evidence and Elaboration. Students are expected to include “smoothly integrated, thorough, and relevant evidence, including precise references to sources and an effective use of a variety of elaborative techniques (including but not limited to definitions, quotations, and examples) . Do the machines recognize “precise evidence” and quotations from sources as support for the writer’s argument? Or do they simply register unoriginal (copied) language and give the essay a zero?

The rest of the high school rubric is troublesome, too. To earn the highest scores, students are supposed to use a “variety of transitional strategies” in their response. Can a computer recognize strategies or does it just count transitions?

Students are expected to include a “satisfying” introduction and conclusion. How can a machine determine satisfaction?

A good essay response will maintain an “objective tone”. How does a computer even begin to recognize tone, let alone determine whether or not it has been maintained?

Students desiring the highest scores need to use “appropriate academic and domain-specific vocabulary” in their response. How can a computer determine if a vocabulary word was used appropriately? Can it even tell if the word was used correctly?

Evidence used in a response must be “smoothly integrated”. A computer can be programmed to look for quotation marks indicating a direct quote from the passage, but can it tell how well that quote has been integrated into the essay?

No, I am simply not convinced that a computer can assess a piece of writing in any fair or meaningful way.

All that aside, there’s another more important concern I have with our students writing for a computer audience. Writing is used to communicate in myriad situations, but at its core, writing is an art form. One of the late Robin Williams’ greatest performances was as the English teacher John Keating in the movie Dead Poets Society. In the film, Mr. Keating challenges his teenage students to see the beauty and power of the written word: “We don’t read and write poetry because it’s cute. We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion. And medicine, law, business, engineering, these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for.” Don’t we want our students to find a creative outlet that allows them to express their true selves? To find some art form, perhaps writing, that gives their lives meaning? I doubt that learning to write a standardized test essay, especially one written for a computer, will encourage any student to explore the beauty of the written word. And if today’s young writers aren’t being encouraged to create pieces that express their unique view of the world, will there be any engaging texts to read in the future? Or will we lose the beauty of a Fitzgerald metaphor, the power of a Maya Angelou poem, the lasting impression of a Dickens first line?

The idea of a computer assessing any art form is ludicrous. Could a computer assess a painting? Perhaps it could be programmed to look for certain colors or shapes, but the overall feeling of the painting would not be well-represented by that analysis. A computer could be programmed to analyze certain chords or rhythms or key changes in a song, I suppose, but none of that would adequately measure the power of the music, the way the song makes the listener feel upon hearing it. To extend an old cliche, expecting computers to meaningfully assess any artistic endeavor would be like trying to comprehend the beauty of the forest by analyzing individual tree branches and leaves.

John Keating also told his students that “No matter what anybody tells you, words and ideas can change the world.” There is a monumental difference between teaching our students to use language in a way that will change the world and teaching our students to earn a good essay score from a computer. I shudder to think of how the testing generation we are producing will view the world and the role of language in it. When they write, will they imagine a lover’s heart being moved by the beauty of their poem? Will they envision a mind changing, a society evolving because of the power of their impassioned arguments? Or will they simply see yet another screen on the receiving end of their writing?

I used to encourage my students to use the introduction of their AIR test essays to “wake up” the human assessor who had probably already read dozens of essays about the same topic. Now, I must teach them to consider how a programmed computer might view their words. And that, I’m afraid, could have a devastating impact on how my students might view the world.

There’s still too much testing

Testing has long been misused to the point where it has lost any potential usefulness in the education of our nation’s children. Questions have been raised by parents and educators not only about the amount of testing that takes place, but also the developmental appropriateness. Then there’s the extent to which test results have created a very lucrative and profitable business market. See The Testing Industry’s Big Four and Pearson Rakes in the Profit.

Since at least 2011, there have been clear indications, cited by Dr. Linda Darling Hammond* in Getting Teacher Evaluation Right of significant errors in the use of Value Added Models in teacher evaluations. See http://bit.ly/getting-teacher-evaluation-right.

We do not need tests to tell us that poverty, inequitably funded schools, lack of access to technology, unaccountable charter schools, trauma, poor professional development, large class sizes and too much time on tests all negatively affect students.

More needs to be done to roll back mandatory assessments to a minimum federal level. That requires that we all advocate clearly and consistently with our elected officials using research and our personal experiences. The opportunity is here. Ask your local to conduct a testing audit. Adopt a resolution to limit vendor testing at the local level. Use all the tools at your disposal — phone calls, letters, emails, etc. — to persuade legislators, state board members and/or local board members on the issue. It’s going to take all of us.

* A Footnote – Dr. Linda Darling Hammond will be the keynote speaker, presenter and facilitator of a panel at the Midwest Symposium on Teacher Evaluation on September 30th at the University of Findlay. Consider attending and engaging further on this topic for change. Registration can be found at https://www.findlay.edu/education/graduate-programs/Midwestern-Teacher-Evaluation-Conference.

Watch OEA President Becky Higgins tell ABC6 what’s missing in Ohio’s report cards.

Tests with More Questions Than Answers

By Julie Rine, Minerva Local Education Association

During the holiday break, I went to the website of the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) to see if more sample test items for the AIR assessment were available. Unfortunately, nothing new had been posted since the initial release a few months ago. For high school English Language Arts (ELA), there are still only seven questions based on two nonfiction readings, and one writing prompt based on three related nonfiction pieces.

During the holiday break, I went to the website of the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) to see if more sample test items for the AIR assessment were available. Unfortunately, nothing new had been posted since the initial release a few months ago. For high school English Language Arts (ELA), there are still only seven questions based on two nonfiction readings, and one writing prompt based on three related nonfiction pieces.

Releasing only a very small handful of questions is unfair to both students and teachers. How can we be expected to adequately prepare kids when we have so little idea of what they will face? Why wouldn’t the state want to release as many sample and practice items as possible to help teachers better prepare our students to be successful on the tests?

Even though we’re not given much to work with, we can analyze what we have. The seven reading questions ask students about the purpose and main idea of each piece, and require them to compare various aspects of the pieces. The single high school AIR writing task that’s posted requires students to read three pieces which show different viewpoints of the same topic, and then use evidence from the pieces to take a position.

I don’t have a problem with any of that. I think it is important for my students to be able to discern the key points of a nonfiction piece and even more important for them to be able to read two opposing viewpoints and take a supportable position on the issue. Gun control, immigration, sky-high college tuition: there are innumerable issues on which Americans hear many voices, so it seems entirely appropriate and even essential that we teach our kids to learn the skill of making sense of the various positions and forming an opinion of their own.

While I am okay with the skills my freshmen and sophomores are expected to demonstrate, I do have concerns about the pieces they will be required to read in order to show these skills.

Let’s see how you would do. Read the two beginnings of the excerpts from the sample items released and tell me how enticed you are to keep reading.

“I know of no more encouraging fact than the unquestionable ability of man to elevate his life by a conscious endeavor. It is something to be able to paint a particular picture, or to carve a statue, and so to make a few objects beautiful; but it is far more glorious to carve and paint the very atmosphere and medium through which we look, which morally we can do. To affect the quality of the day, that is the highest of arts. Every man is tasked to make his life, even in its details, worthy of the contemplation of his most elevated and critical hour.” ~ Henry David Thoreau, Walden

“The first in time and the first in importance of the influences upon the mind is that of nature. Every day, the sun; and, after sunset, night and her stars. Ever the winds blow; ever the grass grows. Every day, men and women, conversing, beholding and beholden. The scholar is he of all men whom this spectacle most engages. He must settle its value in his mind. What is nature to him? There is never a beginning, there is never an end, to the inexplicable continuity of this web of God, but always circular power returning into itself.~ Ralph Waldo Emerson, “The American Scholar”

Can you imagine reading that, with no guidance, when you were 14 or 15 years old and making sense out of it? It is interesting to note that Emerson and Thoreau are part of the common core curriculum for 11th grade, even though the AIR tests will be given in Ohio to 9th and 10th graders. I teach Emerson and Thoreau to my juniors, and once we pull out some key quotes from the pieces and really look at the big ideas, the concept of transcendentalism is actually something they can not only understand, but can find examples of in modern music, movies, and even comics. It takes time, however. If I were to just give them excerpts of work from either of those 19th century authors and told them to read and comprehend them, it would be a daunting task.

The topic of the argumentative writing task that has been released for the high school ELA tests is not much better. Students are asked to read a few selections about whether or not antiquities currently in museums should be returned to their original cultures. I’m guessing that the average 9th or 10th grader taking this test will not be terribly passionate about this issue. True, passion is not required to choose a position and support it, but what would it hurt to choose one of the many current news topics that would be of more interest to the kids and ask them to form an opinion about that?

It seems, based on the very small sample set released as of the end of December for the high school ELA AIR tests, the topics on the test will not be high-interest to teenagers. To be fair, the released writing prompt for the 7th grade ELA test is about the impact of video games on teens’ health. But that is the ONLY topic released for that grade level. The only writing prompt released for 8th grade asks students to read two selections about Machu Picchu and then write “an informational article on Machu Picchu for a website that focuses on travel to places of historical interest”, explaining to tourists “the significance of Machu Picchu as a travel destination”. Many of our students are lucky to have been able to travel out of Ohio, and writing for a website about travel to Machu Picchu, to them, must sound like writing about traveling to Mars.

In getting my classes ready for the test, should I find articles about current topics that are relevant to them and therefore might motivate them to put forth some effort? Or am I doing a disservice to them if I do not prepare them for the tedium of the antiquated topics the test may present? If the topics are outdated or of little relevance to their lives, they will likely lose interest before we even start. On the other hand, if the nonfiction we read in class is something they have heard about or is a topic that affects them in some way, they will be more likely to engage in the activities, and the more engaged they are, the better they will learn the skills I am trying to teach them.

If we must have high-stakes tests to evaluate what our students are capable of understanding or doing, why not make the tasks more relevant to what we want them to be able to do after they graduate from high school? We want them to be ready to analyze the issues affecting our communities and to make informed decisions about those issues. Why can’t the tests reflect that?

It is clear that when it comes to getting ready for the high-stakes tests, we don’t have enough to work with and what we have isn’t usually very relevant to our kids.

“Do what’s best for the kids” is a mantra that gets many educators through the challenge of jumping through various state-inflicted hoops, including the required tests. I have to wonder, though, if doing what’s best for the kids is something that the Ohio Department of Education or our legislators ever consider. Or could it be that these tests are more politically motivated than educationally sound?

I’m trying to prepare my kids for the tests. I really am. But it seems I just keep finding more questions than answers.

Short Tempers and Hard Tests

By Julie Rine, Minerva Local Education Association

It’s that time of year when teachers face two struggles: keeping our tempers, and writing final exams.

It’s that time of year when teachers face two struggles: keeping our tempers, and writing final exams.

Even the best teachers feel stress when the fast-approaching end of the year means getting those final exams ready while trying to finish the units left on the agenda. Meanwhile, kids are gone for field trips, early family vacations, and college visits, so keeping everyone caught up is half the battle. And all this means that what has driven us crazy all year threatens to drain even the kindest teacher’s supply of patience. For me, it’s things like hearing “Do you have a pencil I can borrow?” (because why would one bring a pencil to English class, right?), and of course, the inevitable “Will this be on the exam?”.

Creating final exams is a tricky business. It causes both veteran teachers who have taught thousands of students and the novices to the profession who are finishing their first year to sit down (or collapse, as the case may be) and wonder what their students have learned this year. What did they truly and deeply learn? I’ll admit, some days, I might even ask did they learn anything? This is my own final exam. How did I do in teaching those ever-distracted teenagers, many of whom find nothing relevant to their lives in my class, despite my use of music and YouTube and Chrome Books and Prezis and Power Points and prayers (I didn’t teach them the prayers; those were strictly mine).

The craziness of the end of the year and writing exams leads to a much shorter temper for me. Each April I promise myself I will keep my patience no matter what, and every year I fail. Occasionally my frustration erupts. “Are you kidding me? You didn’t bring paper or a pencil to English class? Seriously?” And every year, as I work on writing my final exams, I wonder if my kids have learned enough American Literature and if I have done enough to prepare them for college writing and passing the ACT.

But this year is a bit different. On a November morning last fall, a car accident took the lives of three of my students. No one was drinking, no one was texting while driving, no one was driving too fast; the roads just turned from wet to ice in no time and their car collided with a school bus. A’liyia, who was a junior in my class two years ago, was a freshman at WVU, loving her first year of college and being the student manager of the women’s basketball team. Storm was a senior athlete who had just finished football season and was getting ready for basketball season. Savannah was a beautiful girl in my 3rd period class this year. Like many kids, she was quieter in class than she was with her friends. I was just beginning to get to know her.

I will never forget getting the news, attending the vigil, or the near silence as kids changed classes the Monday after the accident. So many images are seared into my memory: the looks on their faces, pleading with me to make sense of this for them and my inability to do so; the many hugs and tears our staff and student body shared in those first days; the entire town, it seemed, forming a line around the halls of our school for the calling hours; the gym, normally filled with spectators cheering at a sporting event instead filled with mourners of all ages.

When I reflect back on what my students learned this year, I know they learned more than just English. They learned how to survive a loss so devastating, moving forward seems impossible. They learned that their teachers are vulnerable, and that in some situations, we do not have the answers. They learned that the friends they have known since kindergarten might not walk across the stage at graduation with them. Those are the lessons you can’t put on a final exam.

And when I think about my year, I know that this year more than any other, it was about so much more than the common core and the ACT test. I always knew I loved my students, and I had often said I didn’t know what I would do if I lost any of them. Now I know. I cried for days and found myself remembering all the little moments I had had with each of them that seem so much more meaningful now. I hugged more kids this year than in all my previous years combined, and I cried right along with them when the hand of grief, without warning, reached out and choked us. And, on these final days of the year when the stress gets high and my temper gets short, I have learned to be grateful that an absent student is merely gone for a day or two. I have learned to think before speaking; what I would want my last words to any of my students to be? They would not be something sarcastic about bringing a pencil to class.

I learned that the PARCC and final exams will not be the biggest tests anyone in my school faces this year.

The test we face will not end when the school year ends; it will continue on as our town strives to support each other and the families of A’liyia, Storm, and Savannah, while never forgetting the lessons losing them taught us.

High-Stakes Standardized Testing: A View from the Elementary School Office

by Jenny Russell, Reynoldsburg Support Staff Association

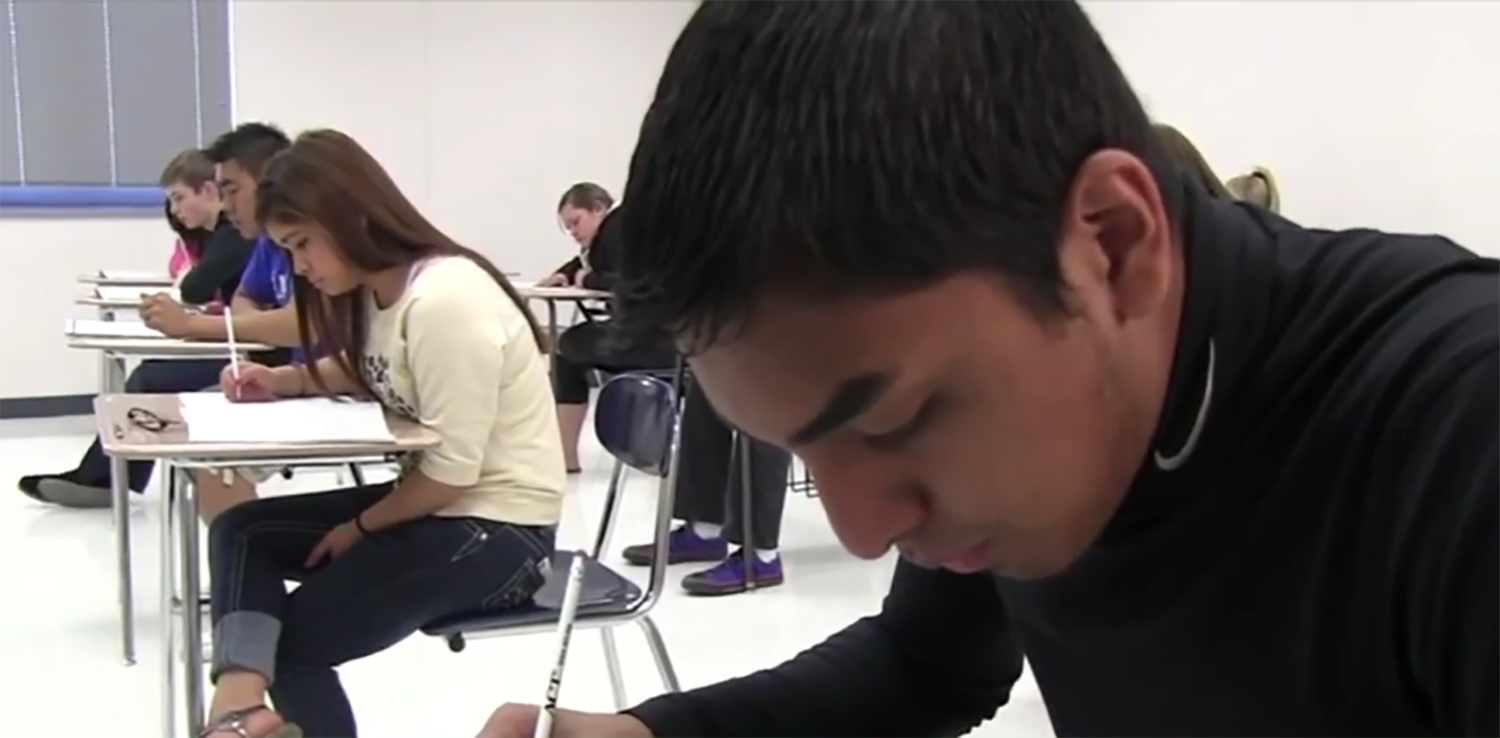

It starts at the very beginning of the day. At arrival, some kids trudge in, others are jittery and anxious. All students start the day in the gymnasium for the school’s daily morning assembly. As the school secretary, I stay in the office, but I can hear the teachers and staff give a pep talk – “You’re going to do great! You’re going to rock the test!”

It starts at the very beginning of the day. At arrival, some kids trudge in, others are jittery and anxious. All students start the day in the gymnasium for the school’s daily morning assembly. As the school secretary, I stay in the office, but I can hear the teachers and staff give a pep talk – “You’re going to do great! You’re going to rock the test!”

But even before the test begins in the morning, I see students in the clinic. “I threw up in the bathroom.” “My stomach hurts.” When I’m wearing my nurse hat, I usually ask, “When did this start?” “When I woke up.” “Did you tell an adult at home? What did they say?” “They said the test is important and I have to go to school.” Lots of parents feel it, too.

Today’s test, or section of a test (most tests have multiple sections and are given over multiple days), starts and ends at a specific time. But in the office, I don’t know if one class starts ten minutes late because they’ve decided to give kids one more chance to use the bathroom, or because they’re waiting for Sally, who is a half-hour tardy almost every day, to show up at school. This means I don’t know exactly when the test ends.

For a half hour, an hour and fifteen minutes, or two and a half hours, there needs to be silence. Often the principal and school psychologist are both administering tests and cannot be disturbed. I send out an e-mail plea for teachers to keep students in their classrooms and not send them down to the office for behavior problems. This is also important because the other rooms in the office suite are also being used for testing – students who receive special accommodations test in these spaces, so the office needs to be quiet during the test, too.

If students arrive at school late, after the test begins (and we almost always get at least one late arrival), they need to stay in the office until the test is finished. Usually they have a book and can keep themselves occupied. Sometimes a parent angrily demands, “Why does she have to sit in the office?” (despite paper schedules, e-mail messages, and even automated phone calls to families the night before, pleading with them to help their children get a good night’s sleep and arrive at school on time because today is a testing day). Occasionally a parent will take their child with them and leave in a huff. But usually, the student(s) and I wait for the all-clear, to let us know that testing is over and they can rejoin their classes.

If students arrive at school late, after the test begins (and we almost always get at least one late arrival), they need to stay in the office until the test is finished. Usually they have a book and can keep themselves occupied. Sometimes a parent angrily demands, “Why does she have to sit in the office?” (despite paper schedules, e-mail messages, and even automated phone calls to families the night before, pleading with them to help their children get a good night’s sleep and arrive at school on time because today is a testing day). Occasionally a parent will take their child with them and leave in a huff. But usually, the student(s) and I wait for the all-clear, to let us know that testing is over and they can rejoin their classes.

After the test is over, I get more clinic visits. Sometimes the kids know they’re truly sick and have just come to school to take the test. This always makes me a little proud and a little sad. Sometimes they tell me that their head started hurting or their stomach started twisting just before or during the test. Sometimes they are not really feeling bad, they’re just looking for a little extra TLC on a stressful day. These usually aren’t my “frequent flyers,” students who I see in the clinic a lot. They’re just regular kids who are stressed out by standardized test after standardized test.

Kids also talk to me about the tests. Luckily, at the elementary level I haven’t gotten any deep questions about why they have to take the tests, although I know they touch on this in their classrooms. They tell me things like, “I’m scared. What if I fail the [OAA reading] test and can’t go to 4th grade?” Or “I’m sick of taking tests.”

They don’t know that these are high-stakes tests. They don’t realize that if many of them do poorly on one or more of the tests, in our district at least, their teachers may be offered probationary contracts instead of standard contracts. They don’t understand that low performance on these tests may lead to a reduction in funding for the entire school.

And I’m glad. Because the ways things stand today, these tests make our students anxious enough.

What to do about too much testing — Fight, Flee, or Fake It?

By Julie Rine, Minerva Local Education Association

By Julie Rine, Minerva Local Education Association

For almost twenty years, I have prepared students in my classes for the Proficiency Test, the OGT, the ACT, and now the PARCC and my own SLOs. Never before this year have I felt that the testing took over my classroom.

Add up the amount of time spent taking the tests, throw in the time spent taking practice tests, and the amount is already eleven class periods, and we haven’t taken the EOY PARCC yet. Toss in the periods we trekked down to the computer lab and the time we spent trying to log in to practice tests and get the technology to work right, and that adds another three wasted days.

And let’s not forget that while I was administering the PARCC to my freshmen, my other classes of juniors had a sub. But the juniors got the joy of taking two pre-assessment and two post-assessment SLOs, which took a total of four periods, so they got to bask in the excitement of testing, too.

And sometimes, just for old times’ sake, I will give my students a test to assess their understanding of a unit over say, Romeo and Juliet or transcendentalism.

The testing is ridiculous. Every teacher knows it, and now with the many issues with the PARCC and AIR tests, parents, too, are realizing that required testing has gotten out of control.

As a teacher, it seems to me we have a few options about how to approach these tests. Some teachers have taken a stand and left the profession, choosing to “flee”, protesting the craziness that education in America has become and refusing to work in a system that subjects our children to the whims of politicians, most of whom have no teaching experience of their own.

Part of me wishes I could do this, but I, like many others in the profession, have invested too much time and money to leave now. And truly, I do still like the kids and the content, but if that ever changed, I would have to seriously consider a Plan B.

Some teachers have chosen to “fight” back, by writing letters to legislators, participating in Lobby Days, and talking to anyone who will listen about how the “game” has changed with the requirement of all the tests, and of course, education should never be considered any kind of a game.

And, some choose to “fake” it, to tell their students that these tests are good for them, that they will help us know what to teach better, that we will get all kinds of really meaningful data that will help improve our teaching. They choose to smile and make the best of the situation and try to hide the fact that this is not what they signed up for when they decided to go into teaching.

I can’t fault anyone for taking any of these approaches. We all deal with adversity in life in different ways. Frankly, at this point we all have to choose whatever path works to keep our sanity. Teaching high school students, and being a generally outspoken and passionate advocate for issues I believe strongly in, I am choosing to fight.

I’m also choosing not to fake it with my kids. I have been brutally honest with my students, telling them exactly how I feel about the barrage of tests now required, and why I think they are unnecessary and take too much time away from actually engaging with each other in discussions about literature and writing and current events … you know, from actually LEARNING.

But, I have also told them that we must jump through this hoop. And we must do our best on the tests, on my part preparing them for the tests, and on their part taking them seriously and persevering even when they seem too hard or too frustrating or too pointless. Because in life and certainly in any job, there are times when you have to do things you don’t want to do.

If you’re lucky, when you encounter those unpleasant tasks, you might find yourself with a little bit of power to advocate for a change. And when the requirements come from politicians, we do have the right to voice our opinions. Part of being an educated person is knowing how to fight back in responsible and respectful ways, such as writing letters to or calling legislators, educating others on Facebook about the issues, and lobbying at the capitol.

Frankly, I don’t care what my students get on the PARCC if they leave my class understanding these much more important life skills. So I don’t fake it with my students and disguise my dissatisfaction with my happy teacher face, and I don’t flee the profession. Instead, I am trying to turn even this, perhaps the greatest obstacle to true teaching I have encountered in nearly twenty years, into a lesson.

That’s the kind of education that cannot be measured by a standardized test.

If you build it, they will come

By Dan Greenberg, Sylvania Education Association

“If you build it, he will come,” whispered a mysterious voice in one of my favorite movies, “Field of Dreams.” By the end of the movie, a corn field in the middle of Iowa was transformed into a magical baseball diamond, where a father and son were reunited, and their relationship was mended through a game of catch.

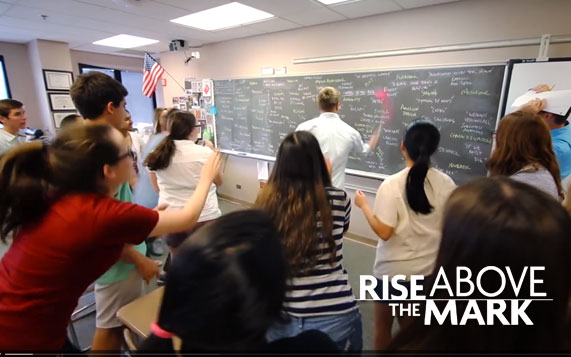

I have no plans to build a baseball field anywhere in Northwest Ohio. However I, along with fellow education advocates in the area, did construct something last week that was like our field of dreams. We set up a screening of the documentary “Rise Above the Mark,” set in Indiana, which chronicles the problems we’re dealing with in public education; over-testing, underfunding and unaccountable charter schools.

We created handouts, telling people how they could get involved. We promoted the event through social media and by working with other local organizations. We set up a panel consisting of two locally elected school board members and an education expert.

We built it, and they came.

They, parents, teachers and community members, came despite frigid temperatures. They came from Toledo, and Sylvania and at least five other school districts in Northwest Ohio. Close to 100 people came to engage in an evening focused on public education.

The audience of close to 100 saw a powerful movie. Some of my friends cried, watching a teacher explain that she’s retiring because the joy of teaching is gone, then later, seeing a father choke up as he tells how important his son’s principal was in his child’s growth.

It was clear, by the attendees’ reactions following the hour-long film, that the documentary struck a chord with them.

Audience members posed questions about how to deal with over-testing, explaining that they didn’t want their kids subjected to hours and hours of PARCC-based questions, wondering if opting their children out of the tests was the best option. Teachers added testimonials to confirm the stories shared in the film. People left agitated, wanting to write to their state elected officials, wanting to know what they could do to help the cause and stand up for public education.

There is no definitive answer. There is no quick fix. However, there is hope, because people from different political backgrounds and different ties to public education came together last week; all of them realizing the importance of a strong public education system. School board members, one Democrat, one Republican, sat next to each other, conveying the same sentiments about the issues facing our schools; both supporting the efforts of educators.

From the success of last week’s event, I know that we must keep building “it;” programs, where all supporters of public education can get together and learn about the issues facing our schools. We must build people’s understanding about the harmful effects of testing by telling stories about children who cry during tests, or about our own children, who can’t sleep the night before a PARRC test, worrying what a sub-par score will mean for themselves and their teachers. We must build an engaged audience within our communities, talking in person or using social media.

If we build all these things, people will come, and they will stand with us, in support of public education.

Our miracle won’t be ghosts emerging from rows of corn. It will be quality public schools for all Ohio’s children.

The Talk

I had “the talk” with my 10 year-old daughter, Nina, yesterday.

I had “the talk” with my 10 year-old daughter, Nina, yesterday.

I wasn’t sure what to say. I didn’t want to explain more than she needed to know. I didn’t want to use words that would confuse her. I was worried that once I explained things, she might tell her friends.

I felt like I had to tell Nina the truth, though. She’s been asking a lot of questions. She even stayed in from recess one day last week to do some internet research. Now she wants to write letters about it.

In case you’re wondering what kind of internet filter my daughter’s school has, don’t worry. We’re not discussing where babies come from. We’re talking about standardized tests.

As I’ve organized community forums on testing, shared articles on Facebook and talked with friends and colleagues about standardized testing, I have resisted telling my daughter my true feelings about the tests she takes every year. I’ve been worried about how she would take that knowledge and whether it would impact her overall love of school and learning.

Things changed this past week, when she told me she wanted to learn more about the tests.

“Did you know we have to take 13 hours of tests this year, Dad?”

I told her I did, trying to conceal my disdain for the tests; trying not to portray negativity about something school related. However, the more I thought about it, the more I felt compelled to share my feelings about testing.

So today, I thought I would show her a three-minute Youtube clip called “Standardized Testing is not Teaching,” by Chris Tienken. The video has excellent analogies. When Tienken explains that standardized test results don’t come back until the summer, he says “…it’s kind of like going for an annual checkup at your doctor, waiting five months for the results, and not being able to know what tests the doctor ran on you.”

I asked Nina what she thought of the clip. Through the ensuing conversation, she made some thoughtful remarks.

“It’s like we’re not really learning anything from these tests.”

“So they don’t count for anything?”

“Why do we even have to take these?”

My favorite, after I explained that teacher ratings were tied to student test scores: “The people who want to judge the teachers should just go and watch them.”

Thankfully, the conversation did not make Nina angry or upset. It made her want to learn more about the tests, so that she can write a letter to whomever she believes can make a change in the testing rules. It’s become a teachable moment, with Nina learning how to search the internet and how to understand complex texts.

It’s ironic that standardized tests and test preparation are the antithesis of authentic learning, yet Nina’s quest to combat them, have created an authentic learning opportunity.

The authentic learning will continue this week, when I take Nina to a screening of “Rise Above the Mark,” a documentary about high stakes testing and other issues facing public schools. I’m excited to see Nina’s reaction to the film, and to continue our dialogue.

I’m glad I had “the talk” with Nina. I hope other parents will do the same with their kids before high-stakes testing season ramps up, so kids understand what they are being subjected to. Maybe these conversations will be the impetus for a whole group of young activists to stand up to the testing culture.

By Dan Greenberg, Sylvania Education Association

'Tis the season for gift giving

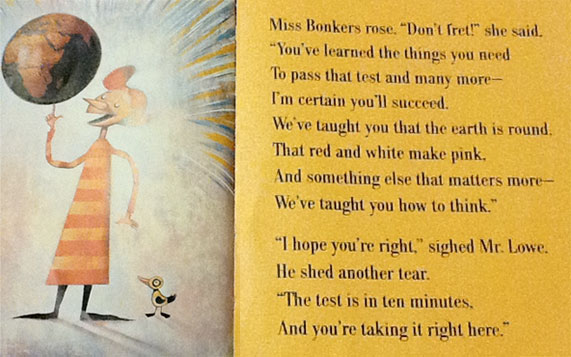

‘Tis the season for gift-giving, and with so many test-driven “school reform” policies being passed at the Ohio Statehouse this year, now would be a great time to present our lawmakers with gift-wrapped copies of one of the most forward-thinking children’s books ever written, Hooray for Diffendoofer Day. This thought-provoking picture book was primarily written by that great American philosopher, Theodor Seuss Geisel, but he died before he was able to finish it. Adding to Dr. Seuss’s original notes, bits of verses, and rough sketches, author Jack Prelutsky and illustrator Lane Smith finished the fable in 1991.

‘Tis the season for gift-giving, and with so many test-driven “school reform” policies being passed at the Ohio Statehouse this year, now would be a great time to present our lawmakers with gift-wrapped copies of one of the most forward-thinking children’s books ever written, Hooray for Diffendoofer Day. This thought-provoking picture book was primarily written by that great American philosopher, Theodor Seuss Geisel, but he died before he was able to finish it. Adding to Dr. Seuss’s original notes, bits of verses, and rough sketches, author Jack Prelutsky and illustrator Lane Smith finished the fable in 1991.

This insightful book is about an outside-of-the-box kind of school staffed by appropriately named workers, such as the nurse, Miss Clotte, the custodian, Mr. Plunger, and three cooks named McMunch. Diffendoofer School teachers provide knowledge-based lessons mingled with some important skills not found on any list of standards:

Miss Bobble teaches listening, Miss Wobble teaches smelling,

Miss Fribble teaches laughing, and Miss Quibble teaches yelling.

The quirkiest teacher of all is the main character in the book:

My teacher is Miss Bonkers, she’s as bouncy as a flea.

I’m not certain what she teaches, but I’m glad she teaches me.

Of all the teachers in our school, I like Miss Bonkers best.

Our teachers are all different, but she’s different-er than the rest.

One day, Diffendoofer’s worried little principal, Mr. Lowe, makes a special announcement:

All schools for miles and miles around must take a special test,

To see who’s learning such and such- to see which school’s the best.

If our small school does not do well, then it will be torn down,

And you will have to go to school in dreary Flobbertown.

Like most of the children in Ohio’s public schools, Diffendoofer students are immediately stressed at the thought of taking such a high-stakes test, and they fret about the prospect of being removed from their beloved school and forced to attend monotonous Flobbertown, where “everyone does everything the same.” They continue to agonize over the test, until Miss Bonkers reminds them:

“Don’t fret,” she said, “you’ve learned the things you need

To pass that test and many more- I’m certain you’ll succeed.

We’ve taught you that the earth is round, that red and white make pink,

And something else that matters more- we’ve taught you how to think.”

Of course, Miss Bonkers is right, and the students get “the very highest score” and pass the dreaded test using background knowledge, combined with the critical and creative thinking skills they acquired through a variety of innovative activities at Diffendoofer School.

The Ohio Legislature’s over-reliance on high-stakes testing for its public schools has forced many districts to re-focus their precious economic resources on hard copy and digital curricula that will aid them in teaching for the test. Could it be merely a coincidence that the same educational companies, that produce the tests and sell those testing resources, also contribute to the campaign coffers of some of the legislators who sponsor the “school reform” laws? One can only speculate.

In this test-driven era, Art, Music, and Physical Education programs are being slashed in many school districts. Field trips are no longer considered affordable. Schools are cutting way back on recess as well, hoping it will “give the students more time to learn what’s needed to pass the tests.” It’s sad to see the demise of activities that round out our students’ knowledge-based learning with important critical and creative thinking, yet these are desperate times for many of our public schools, and they’re trying to get the most test-score bang for their bucks. Unfortunately, this kind of programming will eventually lead to more schools like dreary Flobbertown, where everyone does everything the same.

Before another test-driven “school reform” bill is considered in Ohio, it would be wise for lawmakers to invite public school teachers from around the state to come to the Statehouse to lead a series of book-talks about Dr. Seuss’s Hooray for Diffendoofer Day, accompanied by Diane Ravitch’s book, The Death and Life of the Great American School System: How Testing and Choice Are Undermining Education. Then our elected officials might begin to understand what Dr. Seuss figured out more than two decades ago- continued high-stakes testing is taking its toll on our children, as well as on the institution of public education.

Judging by the lack of teacher input requested by our legislators in recent years, that idea may be no more than another children’s fable.

By Jeanne Melvin, Hilliard Education Association

Tao of the Sockless Floor

High stakes testing is like saying to your child, “I want you to clean your room. I want everything up off the floor and in its place, the funny smell gone, and every surface that can to sparkle. When you’re finished I want you to be able to look around, sigh out of utter exhaustion and accomplishment, and realize this is a room with a future, a bright one. But, at the very least, I want you to pick up your socks.”

High stakes testing is like saying to your child, “I want you to clean your room. I want everything up off the floor and in its place, the funny smell gone, and every surface that can to sparkle. When you’re finished I want you to be able to look around, sigh out of utter exhaustion and accomplishment, and realize this is a room with a future, a bright one. But, at the very least, I want you to pick up your socks.”

For twenty years we’ve been teaching kids to pick up their socks. Our entire system is designed around that minimal level of achievement: our discipline policies, our attendance policies, our curriculum maps, our basic understanding of how schools operate. Everything is designed to get our kids to do the minimum.

But some of us close our classroom doors and do what we need to do. We can see the desiccated pizza slices hidden under the bed. We help the students who want to learn how to organize a closet and arrange bookshelves. Of course some us also got caught, cornered by an administrator who cried, “But what about the SOCKS!”

We point to our data proving our kids can not only recover the hell out of some socks, but also paint the walls and do the laundry like pros. But administrators will scratch and twitch, cajole and threaten, then PIP us back onto the path of true enlightenment: the Tao of the Sockless Floor.

“Look at China’s scores!” say critics of our public schools. To which we point out that China, along with most other countries, don’t try to educate everybody. “Oh yeah? Look at Finland!” retort others. Meanwhile, our scores creep up, but not fast enough. And our funding… What to do? What to do? Tutoring and mentoring and incentivizing and cheating — because you can’t have a school without money.

Maybe some of us believed all along, drank the Kool-Aid and did the enforced bare minimum, covered what we were supposed to and nothing more, drilled children in taking tests, and taught them the tricks of the trade. And because we were doing what we were told, what we were supposed to do, we told ourselves that it was none of our business why our students shuffled in and out of our doors like POWs looking out upon a bare and lifeless promontory where they were going to be made to toil until they dropped (out).

So, school got easier even as the education system at large grew more complicated in ineffective ways, flailing attempts to improve scores. Easy solutions to the problem were offered. Offerings voters should’ve rejected. Despite science, a good chunk of taxpayers’ money is flung at the polished turds of School Choice. Vouchers? Your average private school doesn’t do any better than public ones. Charter schools are a failed experiment. Teach for America isn’t teaching America, and merit pay is without merit.

Here’s a question for you: If the US is consistently behind where you think it ought to be, is it more likely that there is something genetically wrong with each and every American teacher or is more likely that there’s something wrong with the system?

Take a moment. Try to figure out the probability on that one.

I’ll wait.

I think it’s safe to say that most of us grunts in the trenches feel like we’re been trapped inside a farce from which there is no escape, where it’s always the same Spam every day only dressed up in different disguises, rebranded as the next wonder-cure for all that ails the apathetic learner and their burned out instructors. The system is broken. We, who have seen it all before, hide our smiles behind our hands and laugh at them. Forgetting we’re part of that system.

Well, if you’re prepped for surgery and the doctor is about to make a fatal mistake, but a nurse notices it in time, wouldn’t everybody be grateful if the nurse spoke up? And if the surgeon got angry and reprimanded that nurse, you’d still be alive. Sometimes that reprimand is just a reprimand you’ve got to take. That’s part of being a responsible professional. And in this economy, kids’ lives are in just as much jeopardy as the poor jerk on the operating table. It just takes longer for them to pass on.

By Vance Lawman, Warren Education Association – Trumbull County