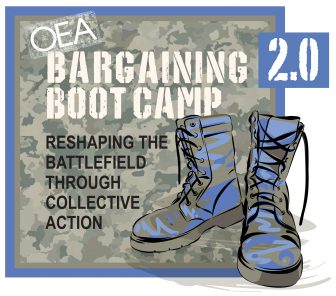

2024 OEA Bargaining Boot Camp

OEA’s Bargaining Boot Camp is an intensive, team-based training offers the opportunity to learn about, and incorporate, essential organizing and bargaining concepts into your local association’s bargaining preparation. Bargaining teams will walk away from this weekend with dozens of tools they can immediately use to prepare for a successful contract campaign including local-specific financial and health insurance information and a core contract language assessment. This year’s training will include both full team training and separate tracks for new participants and those that have previously attended a boot camp.

Check-in for each boot camp will begin at 9:00 a.m. on Saturday and the program will begin promptly at 9:30 a.m. Participants should plan to attend the entire day on Saturday as the program will not end until approximately 8:00 p.m. The boot camp will reconvene at 8:30 a.m. on Sunday and will conclude by 2:00 p.m. OEA will cover the cost of all on-site meals, materials, and single occupancy lodging on Saturday night for each participant.

To ensure maximum participation each boot camp will be limited to a total of 75 participants, including each local’s OEA Labor Relations Consultant (LRC). Acceptance into a boot camp will be based on two factors:

- Willingness and availability of a local’s entire bargaining team to participate in the boot camp; and,

- Expiration of the local’s collective bargaining agreement during the 2024-2025 school year.

Boot camps will be held in four geographic areas of the state on the following dates. A local can apply to attend any of the offerings.

**ALL BOOTCAMPS ARE FULL BOOKED** Watch this webpage for 2025 Bargaining Boot Camps applications beginning Summer 2025.

| DATE | LOCATION | DEADLINE |

| October 26-27 |

Marriott Cincinnati Northeast (Southwest) |

September 20 |

| November 2-3 |

Four Points Cleveland-Eastlake (Northeast) |

September 27 |

| November 9-10 |

Hilton Polaris (Central) |

October 4 |

| November 23-24 | Hilton Garden Inn Perrysburg (Northwest) | October 18 |

Registration will be completed by the “team leader” registering their local’s entire team. To complete the registration, the team leader will need confirmation from each participant that they are willing to attend and provide the following information:

- Member’s Name

- Home Email Address

- Contact Phone number

- Any known food allergies or dietary restrictions

- Whether each participant has participated in a previous boot camp

Click Here to download an information sheet to use with team members.

An email regarding your application status will be sent to the team leader approximately three weeks prior to the scheduled Boot Camp.

Questions? Contact Eric Watson-Urban, Collective Bargaining, and Research Consultant at urbane@ohea.org or Kelli Shealy, Research Technician at shealyk@ohea.org.

This program is offered by the OEA Education Policy Research & Member Advocacy department.

Page Updated: October 17, 2024

Benjamin Local Classified Employees Win Union Election

Joyce Fish loves her students. For 41 years, she has driven the students of the Benjamin Logan Local School District in her familiar yellow bus.

Located in eastern Logan county, near Bellefontaine, Ohio, the terrain can be challenging. “You learn to respect the weather, rugged hills, and steep valleys,” says Dan Fish; yes, Joyce’s husband and colleague.

However, after years of feeling they were not getting any love or respect from district administrators, in December 2017 they reached the Ohio Education Association.

Their efforts paid off — they’re no longer at-will employees and have a seat at the table. Results, tallied July 24, by the State Employment Labor Relations Board, show workers voted an overwhelming 73% in favor of OEA representation.

For the first time in more than 30 years, the district’s 70+ bus drivers, cafeteria workers, educational assistants, and paraprofessional aides will have will have union representation.

They will join the district’s 115+ educators of the Benjamin Logan EA, who have been a part of OEA since 1974.

Joyce and Dan say they’re looking forward to the collective-bargaining process. “Unanswered demands for respect as well as ‘fair and equal treatment for everyone,’ tell a story of professionals who are tired of being pushed around,” says Joyce.

![]()

Oh Yes, We’re Social — Join the Conversation!

Oh Yes, We’re Social — Join the Conversation!

![]()

Collective Bargaining

Without collective bargaining, we can’t advocate for our students’ learning conditions and our working conditions. Being involved in OEA gives us the resources to do that. We believe in public education, we support each other, and, most importantly, we always fight for our students.

The Power of Participation

By Julie Rine, Minerva Local Education Association

W hen I started teaching 20 years ago, some colleagues taught me some very important tricks of the trade: how to get on the janitor’s good side, how to sweet talk the secretary into making last minute copies for me, how to drink cheap beer (on a young teacher’s salary, that might have been the most important lesson!).

hen I started teaching 20 years ago, some colleagues taught me some very important tricks of the trade: how to get on the janitor’s good side, how to sweet talk the secretary into making last minute copies for me, how to drink cheap beer (on a young teacher’s salary, that might have been the most important lesson!).

And then one of those friends invited me (dragged me) to a negotiations committee meeting. I was a member of the association, but really had no interest in getting involved, primarily because I had absolutely no idea what the union did or how it did it.

I remember he said being on the negotiations committee was a good place to start, because one of the most important jobs of the union was to represent the teachers at the table, to work with the administration of the district to make gains that would better serve the students and teachers of the district.

Looking back, I know that he was trying to get younger teachers involved in the work of the local association, as I do now. It’s important that the ideals and goals of the union pass down from one generation to the next and that we keep getting stronger each time the leadership changes. That colleague is retired now, but I think he would be proud of my involvement with the union that all began with one meeting where we brainstormed the needs we wanted to present to the administration at our contract negotiations that year.

Since then, I have served as Vice President and an at-large representative for our local association (we really need a more flattering title for that position!) and I have represented our association on various committees. I have helped screen local political candidates, attended regional events such as the legal update dinner and the annual meeting with state legislators, and last year I participated in the Representative Assembly in Columbus.

“We might be individuals with different beliefs, experiences, and priorities, but together we form a unit to be reckoned with, one that proudly uses its power and strength to advocate for Ohio’s kids.” — Julie Rine

I’ll admit that the first time I went to the ECOEA Legal Update dinner, it was because it is held at a local restaurant known for good Amish cooking and fantastic pies. I still go back every year, but not just because of the pie; it is truly interesting to hear what court cases and legal issues are affecting teachers in Ohio (and frankly, sometimes quite horrifying!).

This was the first year that I attended the dinner with legislators, but it will not be the last.

To actually have conversations with the men and women who have the power to make decisions that affect education in Ohio is an opportunity that cannot be taken for granted. The State School Board members who joined us that night seemed just as frustrated as we are at the recent actions of several members of the Board.

The legislators answered our questions as best as they could, and it was evident that many of them truly have a heart for education and a desire to stop the madness that public education in Ohio has had to endure under Kasich’s leadership.

Not every question we submitted was presented to the panel that night due to time constraints, but every single submitted question was sent to the panel members afterward. Those men and women now know exactly what issues evoke our anger and our passion, and they will be able to better represent us  because of that three-hour event.

because of that three-hour event.

It was by default that I became our local association’s delegate to the Representative Assembly last year. Each spring, my local asks for people to indicate interest in serving on various committees or being our delegate to the RA. No one wanted to be the delegate. We have a very small budget for the delegates, and it’s actually possible to lose money by going to both fall and spring assemblies. I had no idea what to expect, but I and one other colleague agreed to go.

We held the election in the fall to make it official, but we were the only options. Because I was unable to attend the ECOEA RA prior to the one in Columbus, I did not get the delegate handbook until I arrived, but if I were to do this again, I would definitely get the handbook earlier; it explains what will be voted on, and gives many other details that would have kept me from going in blind.

At the assembly, I saw our union in action. There were the usual organizational tasks, budget reports, etc. (and I’ll confess this English teacher might have zoned out on the numbers, but I’m sure the math teacher delegates were paying attention!). What fascinated me most was the presenting of new business, new concerns and suggestions of issues on which the OEA should take an official position.

One of the issues that came up that year was whether or not there should only be one assembly per year, partly because of the financial strain two meetings can put on small districts like mine. On this issue and others, delegates from all over the state and from every local association could and did approach the microphones to make their opinions known, to make suggestions for language changes, and to offer compromises when the supporters of two opposing viewpoints seemed to be at complete odds with each other. The debates were respectful and orderly; a vote was held and the voices of our members were heard.

One way of getting involved in the union that I have not yet experienced is an annual OEA Lobby Day, and I look forward to participating in that at some point. First, though, I better practice a lot more yoga and deep breathing, because I have a feeling it would be a challenge to keep my temper in check if I ever met some of our current legislators.

If you are not involved in your local or district association, I urge you to consider being more active next year. Join a committee, or attend a yearly regional meeting of some sort (if you’re lucky, one with good pie!).

It might seem like just another meeting after school or just another annual event, but every time an association member is active in any way, our power grows. We might be individuals with different beliefs, experiences, and priorities, but together we form a unit to be reckoned with, one that proudly uses its power and strength to advocate for Ohio’s kids.

Categories

About Voices of ChangeCollective Bargaining

Education Support Professional

General

Higher Education Faculty

Higher Education Staff

Legislative Issues and Political Action

Local Leader

Member Stories

Membership

New Teacher

Non-educator

OEA Member

Organizing

preK-12 Teacher

Retired Member

Student Member

Union Business

Equity and Fairness in Higher Education

Is it time for Ohio to revisit the part-time faculty issue in higher education?

In Ohio part-time faculty at public institutions are excluded by state law from the definition of employees eligible to bargain collectively. These adjunct or contingency faculties are teaching as much as 70 to 80 percent of the courses offered by some institutions. Until the passage of the Affordable Care Act many of these part-time faculty members did not have good access to health care.

Two bills were introduced in the 128th General Assembly to allow part-time faculty to participate in collective bargaining, House Bill 365 and Senate Bill 129, though they did not pass.

Over the last couple of years a national organization entitled the New Faculty Majority (NFM) has been established to promote quality in higher education and advocate for the rights of part-time higher education faculty. NFM is dedicated to improving the quality of higher education by advancing professional equity and securing academic freedom for all adjunct and contingent faculty.

NFM is committed to creating stable, equitable, sustainable, non-exploitative academic environments that promote more effective teaching, learning, and research. Adjuncts and contingent faculty deserve to be treated with respect, professionalism, and fairness. Faculty working conditions are student learning conditions.

[quote]Overworked, underpaid adjuncts are also bad for students: Professors who don’t have their own offices, often must work multiple jobs to make ends meet, and sometimes find out whether they’re teaching shortly before the semester starts simply cannot devote as much energy and time to their students as they would like. … We should expect universities to pay adjuncts a living wage, give them benefits and some job security, and provide them with the resources they need to do their jobs well.” — L.V. Anderson[/quote]Collective bargaining is the way toward this goal.

The Mid-Biennium Review calls for Higher Education funding to be tied to student completion of programs and degrees. Is this fair to our higher institutions, including community colleges?

Over the last few years the administration and legislature has been pushing for a state aid formula that is based more on program completion than upon student enrollment.

Around the nation, many states have reduced or flat-lined state aid to higher education. As a result tuition at public institutions have increased steadily. This has only contributed to the national student debt crisis.

The need to find new affordable methods to finance a college education and provide stable funding to our colleges and universities should be among our top priorities.

One national organization has put forth some suggestions. The Campaign for the Future of Higher Education (CFHE) has called for a nationwide discussion of new ideas to solve the funding crisis in America’s public higher education systems.

The authors of three CFHE working papers have presented their ideas in three papers that suggest

- reallocating current governmental expenditures for higher education and eliminating regressive tax breaks in order to provide free higher education to all;

- vastly improving funding for higher education through a miniscule tax on financial transactions, and/or

- “re-setting” higher education funding to more adequate past levels by making very small adjustments in the median income tax return.

They urge you to review these proposals, all of which rebut institutional claims that there is “no money” available to compensate all faculty equitably, and to help circulate them in communities inside and outside colleges and universities in order to generate discussion of practical solutions to the higher education funding crisis.

Weigh in with your comments below.

Equitable Pay: The Underlying Principle of the Single Salary Schedule

Mark Twain once wrote that everyone “has a dark side which he never shows to anybody.” The same cannot be said about our Ohio legislators when crafting the Ohio budget. Their Dark Side is not only visible, it’s so scary even Darth Vader would be loath to join it. It seems the budget bill, House Bill 59 (HB 59), has become a dumping ground for the worst ideas our legislature can think of. One bad idea, among many, is the elimination of the single salary and minimum salary schedules for public school employees.

Mark Twain once wrote that everyone “has a dark side which he never shows to anybody.” The same cannot be said about our Ohio legislators when crafting the Ohio budget. Their Dark Side is not only visible, it’s so scary even Darth Vader would be loath to join it. It seems the budget bill, House Bill 59 (HB 59), has become a dumping ground for the worst ideas our legislature can think of. One bad idea, among many, is the elimination of the single salary and minimum salary schedules for public school employees.

The single salary schedule has been around for nearly a hundred years, having evolved from the inequity of elementary and high school salaries; men were paid more than women, white teachers more than African American teachers, and administrators’ favorites more than equally qualified coworkers.

Eventually, with the help of the NEA, AFT and the women’s movement, the single salary schedule — which prevents favoritism and discrimination by requiring equal pay for employees with the same levels of experience and training — was recognized nationwide as a fair and equitable method of compensating all teachers. Each local union negotiates what those salaries schedules will look like, but in general they reward those who dedicate a lifetime to teaching in our public schools and continuing their professional development through (expensive) education courses.

Then again, that was before teacher and union bashing were in vogue. Now we are living in a society where teachers are bad and unions are the roots of all evil.

Anti-union/anti-public school legislators now want to remove the salary schedules that school boards and local unions have been agreeing to for nearly a hundred years! Among other things, this will allow for some less qualified teachers to be paid more than their counterparts with greater education and experience. Another consequence is that veterans will no longer be remunerated for their years of military service, currently recognized on the salary schedule. HB 59 doesn’t overlook classified employees, or Education Support Professionals (ESPs), either. The budget bill will eliminate the salary schedule for all.

Our legislators also want to eliminate the minimum base pay of $20,000 a year for starting teachers. As it stands, new teachers with a Bachelor’s degree typically earn substantially less than other college graduates just entering the workforce, more than 75% less. I don’t know of any other state that is doing what the state of Ohio is doing — not eliminate-public-unions Wisconsin, not right-to-work Indiana, not even Michigan where school boards are appointed rather than fairly elected. Even the model-merit-based pay Denver Public Schools system has a minimum salary. If that doesn’t inspire Ohio college students to switch out of education majors ASAP, I don’t know what will. And beginning teachers are dropping out at higher rates than most of their students. In 2011, 46% of teachers left the profession within the first five years of teaching. Perhaps our wise legislators are looking for 100% teacher attrition within the first five years.

Everyone will be competing for our limited and precious tax dollars. But unlike the economic business model on which this legislation is based, where businesses reward high performing workers with increased earnings, there is no more money for high performing schools. Public education is not a business. Public education does not turn a profit. We provide a public service in adverse working environments with limited budgets.

Ultimately, the people who will suffer most from this legislation are the children we serve, because teacher quality will go down. Ohio schools will become a revolving door for teachers. Without a voice to protest, our students will be thrown under that proverbial school bus, once again, unless this shortsighted idea is removed from the budget bill. Urge legislators to reinstate the single salary schedule requirement for public school employees.

By Susan Ridgeway, Wooster Education Association

The Puppet Masters

The education community is getting bombarded with new acronyms all the time: OTES, SLO, SGM, etc. Figuring out what they stand for is difficult. Figuring out their impact on public education in the short and long term is nearly impossible.

The education community is getting bombarded with new acronyms all the time: OTES, SLO, SGM, etc. Figuring out what they stand for is difficult. Figuring out their impact on public education in the short and long term is nearly impossible.

However, they are probably missing one very important acronym from their lexicon, one that represents the most influential corporate-funded political force operating in America today, one that has worked to dilute collective bargaining rights and privatize public education. ALEC.

ALEC, which stands for American Legislative Exchange Council, is a conservative organization that develops policies and language that can be used as part of legislation by multiple states across the country.

That probably doesn’t clarify much of anything.

In more concrete terms, ALEC creates legislation for elected officials to introduce in their states as their own brainchildren. ALEC is comprised of legislators and corporate leaders and has been operating in the shadows for about 40 years. They don’t solely focus on public education either. ALEC was the group behind the controversial “Stand your Ground” legislation in Florida, which was at the center of the Trayvon Martin shooting case.

In the documentary “United States of ALEC,” Bill Moyers calls the group “an organization hiding in plain sight, yet one of the most influential and powerful in American politics.”

Moyers’ comment about ALEC is absolutely on point. ALEC is more or less unknown in teacher circles. Teachers, who are focused on their students, generally don’t dabble in the political realm. They have not been interested in knowing or getting to know ALEC, at least until recently.

After the 2010 election — with the assaults to collective bargaining rights, the expansion of voucher programs and education reforms that emphasized testing and “accountability” — teachers in the Midwest got to know ALEC the hard way, though they still probably couldn’t identify it by name.

Think back to those bills that were signed into law in Wisconsin, Indiana and Ohio in early 2011. Ask yourself, how was it that different state legislatures came up with virtually identical anti-labor bills at the same time? The answer: ALEC. The group crafted the language and legislators waited for the most opportune time to introduce it. In Ohio they found it following the 2010 elections when Republicans took control of the Governor’s office and the legislature.

ALEC’s strategy is like the kid’s game of whack a mole. If they were to put out one piece of legislation at a time, education groups and organized labor could easily defeat each one in succession. Instead they toss out a slew of legislation all at once, so there isn’t enough time or resources to educate and mobilize the public. There is no way to effectively beat back all the reforms.

In “How Online Learning Companies Bought America’s Schools“ Lee Fang summed up ALEC’s strategy: “spread the unions thin ‘by playing offense’ with decoy legislation.” Spreading the unions thin has resulted in radical changes to classroom teachers’ everyday lives — changes that were made without the input of local school boards or educators.

As states have expanded voucher systems, schools have had to drastically reduced funding. These programs take money away from traditional public schools and give it to unaccountable and very often less effective private and charter schools. This means larger class sizes for us, less extra help for students and fewer electives.

They have also increased standardized testing, bringing with it the stress that goes along with constantly prepping students for high stakes tests. It’s frustrating because we all know that these tests are not a true indication of students’ progress and understanding. And now teachers are also experiencing the stress of state-mandated teacher evaluations.

These ALEC-induced policy changes have devastated teacher morale and driven many to retirement.

It’s astonishing how much impact one group can have without 95% of the public even knowing it exists.

By Dan Greenberg, Sylvania Education Association

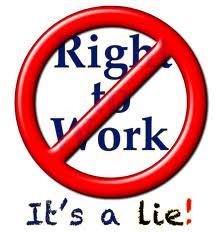

Stories from the Front: Working in a RTW State

In a world where people misconstrue and twist information to fit their needs and agendas, it’s hard to know who and what to trust. Quotes and video footage get taken out of context. Athletes and celebrities swear up and down that what they are saying is the absolute truth, only to admit to their wrongdoings later.

In a world where people misconstrue and twist information to fit their needs and agendas, it’s hard to know who and what to trust. Quotes and video footage get taken out of context. Athletes and celebrities swear up and down that what they are saying is the absolute truth, only to admit to their wrongdoings later.

Take my recent trip to Lansing, Michigan last month to attend a rally protesting the “Right to Work” (RTW) legislation Governor Snyder signed into law. After seeing footage of a physical altercation between labor protestors and Tea Party activists on the lawn of the Michigan Statehouse, my family and friends reacted with sincere concern for my safety. Based on the Fox coverage they had seen, which depicted a chaotic and dangerous situation, they questioned my decision to be a part of the “riot” up there.

In reality, it wasn’t a huge deal at all. Only a handful of the over 13,000 protesters in attendance were involved. A tent came down. There may have been a punch thrown, but I wasn’t close enough to see. The incident only lasted a few minutes. The bulk of the day was spent listening to speakers, chanting and commiserating with Michigan workers about the state of affairs.

Despite the fact that what was shown on TV was a total distortion, that’s what most people are going to believe.

Knowing how often things get sensationalized, I work hard to find reliable sources for information. With a RTW group petitioning to put a Constitutional Amendment on the November ballot, I need to find information I can trust, so I can form an educated opinion. What I’ve found is that the most reliable and meaningful information has come, not from newspaper articles or television shows, but from other educators. Listening to their stories about what it’s like to teacher in states with RTW laws has given me the insights I need to understand why these are harmful and what I can expect if they are enacted in Ohio.

The person I turn to most often is my friend and colleague, Perry Lefevre, who has taught for over 25 years and has been a leader in my local education association. Perry told me what it was like to teach in Waco, Texas upon graduating from Baylor University. “I caught my principal, a family friend, formally evaluating me from the hallway,” he said. “I had a final grade changed on a problem student by the same principal because he was the star running back and wouldn’t be able to play in the fall with a failing grade. And the superintendent/treasurer tried to force me to drive a school bus before and after my school day. My contract was literally a single page in length.”

Unlike Perry’s situation in Texas, my district, under a collectively bargained contract, has set up a procedure where principals have conferences with teachers before a formal observation of the class. The principals take the time to understand the context of the lesson, and listen to teacher concerns about areas in which they would like to approve. The evaluation becomes a useful tool to help teachers improve their delivery of instruction, not as a means to reprimand teachers and tear them down.

The wife of one of my colleagues had the same type of slim contract as Perry in the two public schools where she worked, in Georgia and Alabama, both RTW states. “The contract was not very detailed,” she said. “It was basically stating your employment for that year and consequences if you left early that year.” Describing her experiences in Alabama, she said, “There were some days were we did not get our plan, because of scheduling/ events. There were no real consequences for office referrals. Most of the time, the principal would call their parents to let them know what happened, but even that did not happen all the time. Students were able to cuss at you, flip desks —I even had a girl flash the boys to show them her new bra —and they would be back in your room within minutes and no real consequences was given. We had to cover our own recess and we were also required to eat in the cafeteria with the students to monitor them. We were the only monitors in there.”

In contrast to her one-page contract, my district has a 100-page, thorough contract. This lengthy document works well, because it outlines many procedures and sets parameters for wages and working conditions. It benefits both teachers and administrators, as it establishes a framework for the way schools will operate. It’s a collectively bargained document, so teachers and administrators are able to create this document together. With this contract, teachers in my district don’t lose their planning time, which is a crucial part of the day.

Then there’s Brenda, who taught in the RTW state of South Carolina for 34 years. I was struck by the discrepancy in teacher pay between Ohio and South Carolina. Brenda’s salary after 34 years of teaching is less than what I make after 15 years of experience in Ohio. In fact, teachers in my district with 34 years experience make about $20,000 a year more than Brenda. Brenda explained there was no real salary negotiation in her district. It was more about teacher association leaders “pleading” for a raise. If the administration said there was no money, then raises weren’t awarded, and there was no recourse.

Reflecting on the conversations I had with these three different people who taught in different RTW states at different times, one thing becomes apparent: Teaching in RTW states is a frustrating experience for public school educators, far more so than for us here in Ohio, where teacher associations work collaboratively with administrators to improve schools for students and educators. But that because we don’t have RTW legislation blocking our ability to fairly and collectively bargain for our students and ourselves.

I take the words of my fellow educators to heart. I know I can trust their first-hand accounts, far more than I can those who consider RTW the correct path for Ohio and our public schools.

By Dan Greenberg, Sylvania Education Association

Supporting Charter School Educators, Not Charter Schools

As a delegate at the 2012 OEA Spring Representative Assembly, I was honored to be part of the official governing body of the OEA, and it was also good to see old friends and debate new ideas.

As a delegate at the 2012 OEA Spring Representative Assembly, I was honored to be part of the official governing body of the OEA, and it was also good to see old friends and debate new ideas.

The delegates made several important decisions this year. We elected a new Secretary Treasurer, Tim Myers of Elida EA. We supported the Voters First Initiative to reform the redistricting process to be fair, open and honest. And we also voted to begin organizing charters.

On my way home to Akron, I spent most of the drive thinking about the latter decision and the debate leading up to it.

One member opposed to the motion stated succinctly, “Can we organize teachers in the very schools we have advocated against?”

The thought had crossed my mind as well. How do we organize teachers who are not held to the same accountability standards as traditional public school teachers? How do we push forward our agenda and ask for equitable funding for both school models when there are such vast differences?

Ultimately, the answer to these questions occurred to me: It won’t be easy, but it can be done.

Charter schools are not going to go away. The National Alliance for Public Charter Schools (NAPCS) announced at the end of last year that the number of students attending public charter schools across the nation has surpassed two million.

So, as long as charters exist, shouldn’t those teachers be licensed and given compensation equitable to their public school counterparts? For the last few years, different groups across the country have begun organizing charter school unions and we can learn from their efforts and mistakes.

And here’s the other thing that may not seem related at first. There are many public officials who are happy to see OEA become smaller, even though it’s caused layoffs caused in turn by massive school budget cuts. Why? Because they want to bust the unions and silence our collective voice. We learned that with SB 5 and Issue 2.

What does that have to do with organizing charter school employees? Because the smaller an organization we become, the less influence we have to help elect responsible legislators who support a positive agenda that puts students at the center of reform, who want to invest in classroom priorities that build the foundation for student learning and who want to ensure that every student has a qualified, caring, committed teacher — in short, elected officials who support reform for our failing charter schools. Organizing charter school educators is both the right thing to do and necessary to us as an organization.

Even if I don’t agree with our state laws governing how our charter schools are run, I am a teacher and a taxpayer. I can’t ignore that teachers need improved working conditions and better pay, and students need innovative learning environments. In the long run, students, teachers, and citizens will benefit from organizing charter schools in Ohio.

By Susan Ridgeway, Wooster Education Association

We deserve to be at the table, not on the menu

Jumbo shrimp. Civil war. Freezer burn. A fine mess.

These are examples of oxymorons, expressions that combine contradictory terms. I discovered a brand-new one when I read a recent article referencing the governor’s yet-to-be-unveiled education overhaul plan.

The plan actually doesn’t belong to the governor so much as it belongs to Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson. Sen. Peggy Lehner, R-Kettering acknowledged that Jackson’s plan contains many provisions that were “also in Senate Bill 5.”

Then she unveils her oxymoronic creation. Jackson’s plan, says Lehner, “…takes the best of Senate Bill 5.”

The best of Senate Bill 5 was than 1.3 million Ohioans signed petitions in less than two and a half months to send a message to the extreme politicians that passed the bill, that more Ohioans voted AGAINST SB 5/Issue 2 than voted FOR the governor who campaigned for it and that the 2011’s election turn-out was the largest in more than 20 years of Ohio election history.

Ohioans in the crosshairs of Senate Bill 5 fought against it because politicians rammed it through the legislature. Instead of being asked about what systemic changes should be made, we were told “This is how it’s going to be from now on in Ohio.” The legislation’s passage helped make We Are Ohio into an effective, dynamic organization that achieved its single goal—the repeal of SB 5.

This is an example of how the relationship between any school district and its teachers should work. Both sides share the same goal; to ensure their students’ success, but neither side can do it alone. They’ve got to work together. Unfortunately, this isn’t the case in Cleveland right now.

Rather than speak with the Cleveland Teachers Union about his transformation plan, Mayor Jackson held back-door conversations with city’s business community. Instead of putting teachers at the table, Jackson’s plan puts them on the menu.

Some his ideas sound strikingly similar to Senate Bill 5. There is a curiously strong focus on collective bargaining, and it is reminiscent of a letter Jackson wrote to legislators in June addressing his requests for the state budget.

The mayor knows that his transformation plan won’t happen without the assistance of the governor and the Ohio General Assembly. “Quite simply,” Jackson writes in this plan, addressing state legislators, “we cannot do it without your help.” The governor got Jackson’s message and is watching.

“I’m counting on Cleveland to deliver the goods,” said the governor in his 2012 State of the State address, adding, “Oh, I’ll work with them. I’ll go door-to-door to every one of their offices.”

What happens in Cleveland will have statewide implications for us all. We must make legislators realize that collaboration is key to the success of our students. We must refuse to be cast as the villain. We as teachers are part of the solution, not part of the problem.

A fine mess indeed.

By Phil Hayes, Columbus Education Association